Driving the Labyrinth

2014 Travel Journal: Austin, Houston, Oklahoma, and the Journey East through Missouri, Illinois, and Indiana

I am pretty much running these journal entries without much editing to capture the mood and time twelve years ago, though some of it gives me pause. I have also cut several pages about the conflict in Oklahoma, and it still seems way too long, especially this many years later. I also don’t have the photographs, except one mysteriously, which I included. They begin again, equally mysteriously, in Montreal. I still have hope of recovering them by going back to 2014 on Facebook where I posted them, but I don’t as yet know how to do that or if they will really be there.

Austin

I began writing these travel notes in medias res and, from the responses (in 2014), I have picked up a few readers via Facebook and other sharing portals. Thanks to everyone who sent me their insights or encouragement. I want to emphasize here just how bizarre and radical this trip is for us. We spent most of a month packing up and/or discarding four decades worth of accumulation from our Berkeley life, some of it even older than that since it came west with us from Vermont with our two young kids who are now 45 and 40 with kids of their own. As the days passed, our house gradually became less and less a residential space and more a warehouse with stacks of boxes: 18 x 18 x 18, 18 x 12 x 12, 24 x 18 x 18. Then on June 25th two movers arrived at 8:30 AM, having parked their truck in the street. Two others showed up soon afterward in cars, and then they began their routine. They were equipped with pads, hand trucks, and their own packing materials. In one day the house was emptied and became lonely and hollow-sounding, as though it were a space for rent. Seventeen years of accouterments and habitation were gone. What remained were a few objects that the new owners had bought from us plus stuff for either Salvation Army or the edgy and preferable (but less reliable) Charity Squad. There were also a few items that the movers flat-out missed, while they were also mistakenly loading some objects meant for either donation or the dump. Neither outcome was reversible any longer: the doors were sealed either way. On Lightning Vans’s storm through our house, four people worked in hyperdrive, hauling somewhat indiscriminately and then, since they had skipped lunch (no fast-food joints near enough for their satisfaction), they wanted to be out of there at six sharp. We were astonished that it did not go exactly as planned. Who wanted to ship junk 3000+ miles for no reason or randomly leave behind items we valued?

It can be hard to picture what something is going to be like before it happens. We just assumed that the meticulousness with which the salesman went through and itemized everything along the tags that we placed squarely on stuff that was not to be loaded would suffice to assure a perfect match. But that did not account for the distracted haste with which they worked or the language barrier (all Spanish—they couldn’t read the “Do Not Move” tags).

As he surveyed the rather obvious errors with us, Lightning’s foreman concluded that it would be cheaper for us to let the cargo go as packed; that is, we could replace the overlooked chair, rug, bureau, etc., on the other end, and discard the grungy futon, etc., for less cost and less collateral damage than we would incur having the men take apart and rearrange the entire load. It still grates on me, but less and less as time passes. I take in the deeper meaning of being “between worlds,” not attaching to objects that sooner or later have to be let go of anyway. That is a lot what this trip is about—a detour from everyday patterns, a turn in the larger road.

So Lightning Vans made their hit-and-run and put our load in storage in San Leandro. I verified that by email exchange with the salesman the next day. Initially he didn’t understand what I was asking him (“Do you have our stuff? Were those really your crew?”). I had seen enough episodes of Mission: Impossible! to not take for granted possible subtexts behind a bunch of unknown guys showing up in uniforms, clearing your house of all your belongings, putting them in a rented van, hitting your credit-card for $5000, and then disappearing into the dusk with mariachi music on the radio. Once he grokked the true range of my paranoia, the salesman wrote: “Yes, our crew picked up your goods yesterday and they are safe in our storage location in San Leandro. We did receive the payment as well.”

We had stayed and ate that night two blocks up the hill at the house of an out-of-town friend, also the contractor who had worked on upgrading our property for sale. The next day the couple we hired to clean arrived promptly after breakfast. Lindy had found the husband-and-wife team on Craigslist though not as cleaners: they arrived as potential purchasers of a small kitchen bureau and then asked to look around and selected assorted other items for themselves and family members as well. They came to collect them in a fancy truck and paid with 7 $20 bills. When I saw the vacuum cleaner and chemicals in the rear as we were loading, I asked and José replied in the affirmative, “Yes, we clean. We do everything.” Then Lupita proudly produced her string of clients’ keys. She pulled them out of her purse like clowns’ handkerchiefs, and I am going to guess that there were fifty, maybe even a hundred, all braided together in what looked like an Inca counting knot or a motley strand of a dreadlock with found jewelry. That was her response again when Lindy asked for references: the keys. She said nothing but moved them closer to Lindy and shook them. She had a proud, almost imperial smile. “There they are,” I said. “The keys are her references.”

After José and Lupita finished their whirlwind of cleaning, we got on the road by 1:15, heading for LA, just like that: June 1977 in; June 2014 out. Most of a lifetime in between. It felt like a getaway because it was, and in that sense it was thrilling.

I think that part of me always wanted to get out of California and vamoose onto the highway going east, from the time we arrived for “one year” and then “for good” in ’77, but things got complicated very quickly with young kids and the onus to earn a living. Real life had hit; we were no longer a young couple in a post-college enchantment with cute babies and who might find college teaching jobs forever. No jobs had materialized; our natal families were in various states of dysfunction themselves and offered no support or backup. We had to do it ourselves. And it suddenly came together in countercultural Berkeley with North Atlantic Books in a way that had never occurred to us or been possible in Maine or Vermont. In the Bay Area people with upscale educations like us didn’t just look around or beg for college teaching gigs; they invented businesses, whole new realities. By the time we headed out of town, we left behind a fully operating publishing company with twenty-five employees, albeit in a bad era for the publishing business with predatory Amazon on vulture watch, plenty of DIY technology in competition, and too much free reading material on the Internet.

But the eighties, nineties, and aughts were great for small independent presses, spurred by a change in inventory tax laws (driving commercial publishers into the bestseller business and out of more specialized and serious lines that we were developing like internal martial arts, bodywork, and shamanism), the emergence of the imprint-blind chain-stores (and early Amazon) who cared more for the discount rate than publishing-insignia prestige, and the development of large-scale independent distributors that allowed smaller presses to compete with larger ones on the same terms and turf—we used Publishers Group West for almost thirty years before switching to Random House in 2007.

Yet for all that, in some essential way Berkeley never seemed quite real to me. It lacked summer thundershowers, evening fireflies and August heat, fall chill and colors, first snows and then first lupines and forsythia.

What the Bay Area lacked in the depth of an internalized seasonal zodiac, it made up for in psychospiritual training, lifestyle, and alternative-career livelihood. I remember how shocked Lindy’s mother was by the turn of fate. To her death, I don’t think she ever quite believed that what we were earning was “real” money; it looked too easy, too much like mischief and fun. We were just doing our weird stuff and were suddenly earning many times what we did in our teaching jobs. Yet we weren’t being doctors, lawyers, lumber barons (like her father), or financiers. I wonder what she would have made of retired dot.com millionaires in their thirties, some of them down the block or across town from us—but she didn’t live that long. None of it would have seemed real by her old Colorado values.

Through the rich, complex decades of my thirties, forties, and fifties, I barely noticed Berkeley’s lacks, as northern California provided wise friends, mild winters, and lively ethnic restaurants while it trained me in meditation, diet, martial arts, palpation, energy perception, conscious breath, psychic awareness, and, perhaps most significant of all, gave us a way to turn something I loved and was good at (writing and publishing books) into an entrepreneurial endeavor and honest salary. Those were true, hard-earned skills, from the craniosacral stillpoint, sitting Zen, and internalizing a hsing-i set to how to co-venture book projects.

The reason that such an entrepreneurial scenario never would have occurred to me in Maine or Vermont (or New York City) is that too much in those places was fixed, resolute, and impenetrable, guarded jealousy by prior generations. Youth culture was an oxymoron. But the spaciousness, open-ness, and big, sunny skies of Berkeley welcomed and initiated me, and it entertained both of us for the greater girth of a human life.

By the time we left, Berkeley was no longer Berkeley, and the transitionfrom hippie to yuppie to techie had its own irreversible momentum—this is a millennial regional shift like drought itself. In Beserkley’s geographical slot is a new city in a new century, the traditional avatars and seers pretty much gone, the Telegraph Avenue shops (except for Lhasa Karnak herbs) having withered and then died on the vine: the many bookstores, art studios, cutting-edge therapy centers, and psychospiritual sanctuaries. You wouldn’t find Paul Pitchford transubstantiating a bottle of tap water in the sun in an apartment on lower Woolsey Street as I did in 1975. You couldn’t drop your kid safely into the melée of Derby Dump. You couldn’t hear shamanic drums answering each other across Tilden Park. In the place of Peter Ralston’s School of Ontology and Martial Arts sits a staid antique shop.

Beserkley 1977 was a numinous city. As a friend’s answering machine put it, “I’m either on another line or out of my mind.” Berkeley 2014 was suburban Silicon Valley, a burgeoning Orwellian dystopia that a native friend later renamed Zombierkeley.

Meanwhile the territory we left for the cutting edge out West now feels cutting-edge anew: northern New England, Maine, Portland itself, NYC (Brooklyn/Park Slope, etc.). So a getaway…yes. A less dire version of Tim O’Brien’s Going after Cacciato, a transit from California to Maine in relative peace instead Saigon to Paris in wartime—state by state, province by province, reality sphere by reality sphere, Tree of Life to Juarez to the Inn at Baron’s Creek.

It was propitious that each of the songwriters whose performances we attended the second and third night in Austin, Slaid Cleaves and Dave Insley, dedicated a number to Richard and Lindy, on their road trip from California to Maine. As Dave put it, “You’all been staying there part-time, but now you’re going for good, right?”

Nods from us. “Um huh.” Or sort of, but no one needs to know either the paradoxes and complications of our plan.

We were slow to get out of Fredericksburg the next morning, lolling till the maids hit the room at 11 (that’s how these blogs get done). Then we searched out one of the exalted peach-farm stands outside of town Austin-way to buy a sackful for our hosts. Our home-exchange.com partners already had family in the Mount Desert area, so the trade, instead of house for house, was for (on our end) books from NAB about Maine plus Fredericksburg peaches purchased on 290 on the way.

It was 70.5 miles from the Baron’s Creek to Jack Allen’s restaurant, situated about half a mile east on 71 from its juncture with 290. That’s where Robert Phoenix and his girlfriend Katey had arranged by cell to meet us for lunch. It was Robert’s regular hangout and so-called watering hole, only an eighth of a mile from his apartment and the stage for his online talk show featuring astrology, cosmic and local conspiracies, the general occult and weird, and pro sports, plus their intersections, often weird in their own ways.

I love Robert, but I didn’t love Jack Allen’s. I don’t care if, as Robert carefully explained, the owner (whose name isn’t Jack) is in partnership with Nolan Ryan and has a comparable establishment with him in the Round Rock Express baseball stadium. The food came off the menu and out of kitchen like something that Nolan Ryan would preside over. The waiter (and the waitress who replaced him mid-shift) were overwrought performers of what must have been a brand of Texas hospitality but felt to me like half-hearted vaudeville. The semi-edible fare was essentially Denny’s with a California-cuisine booster, the boost being menu language more than food. I forget what I found to eat, but I believe it centered around likely-pesticided vegetables. But I don’t want to be obnoxiously cynical. It’s just that Robert is a very radical bloke in most things, but as far as pro sports, diet, and interaction with the public go, he follows a mainstream denominator of his lineage. He honors his working-class roots, which are real things and not washed away by any degree of counter-cultural overlay. He likes his nachos and comfort food; he’s an extravert too, a player and volleyer of improv. He enjoyed giving back as freely as he got with Jack Allen’s crew, so the service surged to high theater. Plus his pining for a boysenberry whipcream event not on the menu that day blew any further cover he or the waiter might have had. At Jack Allen’s (and we all have our Jack-Allen-like addictions), he was a delightful and shameless sellout, a lovable downhome big-boy.

After lunch we followed Robert and Katey to his apartment complex. This was an unexpectedly spiffy affair (given his arrangements in Berkeley) of a sort that turned out to be endemic to thriving urban Austin—communal living without ideology. It was an upscale condo village maintained at a luxury level relatively inexpensively by locating many services in commons rather individual units. First we stopped at the business-center commons where Lindy and I were able to catch up on printing, scanning, signing, and emailing. Then we went to the apartment where Robert’s pair of indoor-only cats were hanging out, perhaps awaiting the return of the friendly primates, as they immediately became interactive. Later all four of us went to the complex’s pool commons where we sat on chaises in the super-bright super-hot sun and continued our quickly segueing conversations. The bathing zone was an ingenious miniature-golf-course of a pool with sectors, islands, and connectors, adults and kids frolicking as though it were still the fifties, only better, which is 2014 Texas in a way.

Mr. Phoenix is a special guy. I met him in, I believe, the mid-90s after North Atlantic was told by Publishers Group West to stop freeloading and get its own warehouse. PGW then arranged a shotgun marriage between us and Conari Press, and together we rented one of the extra Tenspeed warehouses owned by publishing and real-estate mogul Phil Wood. Because space was about 20,000 square feet, 5,000 too many for the two of us, we sublet sectors to six other presses, creating a small city or publishing mercado. The funkiest of the tenants was a magazine, Mondo 2000, and their music editor immediately moved in with his dog.

Will Glennon, the publisher of Conari, came to our office to inform me of this dilemma one day and suggested that I might volunteer to go tell him to leave since we weren’t zoned for habitation and Mondo wasn’t paying enough rent to house employees anyway. “He’s a huge guy,” Will said as if that explained anything.

When I got there, Robert charmed me in thirty seconds flat. I found that he was not someone to kick out but a national treasure, we were privileged to have him there. As he put it, “You’ve got a night-watchman, full-time, no charge. And my dog Cosmo is psychic and reads tarot. Where else can you get that for free?”

How could we “evict” this guy?

Robert and I have been close friends since, as we share the classic if all-too-rare complex of the occult, conspiracy theories, politics, music, and pro sports. He can handicap Sunday football, talk NBA and the Oakland A’s, read tarot for the San Francisco Giants’ announcers (and at big computer company Christmas parties, flown to and from California for such gigs), single-handedly move a gigantic desk into our house (around 1998), and tell you every Kennedy Assassination theory (later intricately interwoven with 9/11 synchronicities) and chemtrail/alien-brain-on-the-Moon conspiracies. Since we met, he has brought numerous quirky authors to North Atlantic, the main one being international channeling star and sea-mammal familiar Patricia Cori, an American living in Italy.

At the pool I asked him about the company at whose annual Christmas bash he reads tarot for individuals, and he said, “Your computer falls in the bathtub or get burned in a fire; you have anything left on the hard drive, these folks will get it for you. It’s not cheap, but then they can afford tarot readers at their parties.”

After Mondo folded, Robert went to work for a music website, met a woman at a staff party in San Diego, got married in Vegas maybe not that very night but not a whole lot later, had a son Griffin (who is now ten), and was coaching him in Berkeley Little League when his by-then ex-spouse and her new partner decided to move to Austin so she could take a job with Lance Armstrong’s Livestrong Foundation, at exactly the wrong moment (for Lance anyway). “I was finished with Berkeley,” Robert confessed. “I was waking up there with no interest, no will to do anything. Like every fucking day. I was fried. I had to get out before I passed on in my room.”

Later, he riffed off an earlier blog segment, saying “This is about the transmigration of souls from Berkeley, Richard. You and I aren’t the only ones in motion, my friend.”

Robert remains inimitable, of course. Such folks stay in one groove or another. His present partner, Katey is Celtic, from England, raised in Italy, has a PhD in physics, and is a professional energy healer and psychic. She lives and practices in San Diego but visits him in Austin regularly.

All afternoon Robert kept up a steady banter regarding cats, chemtrails, the For Lease and For Sale signs on Highway 35 between Austin and San Antonio (“You won’t recognize it in five years, the two cities are coming together”), sparrows with a nest of six babies on the spigot for the emergency sprinkler system on his deck (Lindy ironically worried about them getting enough water, so he cut up a plastic gallon jug on the spot, filled it with water, and set it outside, christening it “Lindy Springs.” I mean, Will, did really want me to evict this guy?)

Outside by the pool, Robert continued with an analysis of Jason Kidd as a super-Aries, how lucky the Nets were to get rid of him now before he destroyed the team. “He’s an over-the-top Aries, so he can’t control his actions. He’s power hungry and a genius, but he doesn’t understand it, which makes him really dangerous. I’ve done the guy’s chart.”

He might have discussed this matter anyway, but it was put in mind by my wearing my Scottsdale-mall Brooklyn Nets cap to the pool, the Arizona (now Texas) sun being too hot and unforgiving not to put something on my skull—I was getting lightheaded from the burn. Robert looked at it and, without prologue, read its tarot aloud.

He also brought up the outrageous notion that Richard Hoagland got his information about Mars and the Moon by being Arthur Clarke’s secret lover (not Robert’s idea—he was passing on a rumor that someone else had started). I told him that Hoagland was an old-time vintage “lady’s man.” Katey offered that that might be a cover, but I said, no, in Hoagland’s case, it definitely wasn’t a cover. But Robert’s net is wide, and he gets the full complement from nutty to brilliant

We next touched on El Paso, which Robert called a model for the future American city: lots of people in one another’s vicinities operating under the radar or any government interference, no boundaries either internal or external as the megapolis spread legally and illegally across the desert: Indian casino money mixing with Mexican drug-cartel money (“check out the McMansions in the hills built by people with downtown shops lacking any real products”), all that nouveau riche mixing with old gringo ranch wealth. “The entire country’s going to be a version of El Paso someday. It’s the future, in fact the most radical urban scene going.”

“I guess that New York and LA haven’t noticed.”

“They will. In fact, they don’t know it, but they have.” In fact, it was the already the basis for the FX crime drama The Bridge. We had just walked across that bridge.

Our largest amount of time was spent on an analysis of Griffin’s current baseball coach, a sociopath Robert attested. I won’t go into all the details of the coach’s lies and misdemeanors, but for instance, Griffin had gotten stitches for a ball smashed at him so hard during a practice that it melded his lip to his teeth and he had been denied his rightful shot at being game captain time and time again, likely because he plays the same position (third base) as the coach’s son.

Robert explained all this in terms of Carlos Castaneda, a fable he was also tailoring for Griffin. “The guy lacks an assemblage point. He’s closed. There’s no way to get to him. I told Griffin to tough it out. He’d be stronger for it. But where there’s no assemblage point, a person is not educable or changeable. Plus there’s lots of politics in Texas kid baseball as it is. Some teams recruit ringers from Waco or Laredo, and a kid who’s better comes along, the other kid is gone; that’s what we’re competing against. Some of these teams from Laredo and the border, the ten-year-olds are shaving.”

We headed to our place at 6:00 PM to meet our hosts. I should explain that in May I had suspended our homeexchange.com listing because I was tired of telling wannabe exchange partners that we had sold our Berkeley house and were leaving town (we almost never got inquiries for our Maine house). However when our house sale got pushed later into June (as the first potential buyer bailed after reading seismic and inspection reports), our Austin connection for a place to stay also fell through. The window for David Lauterstein at either his massage school or house passed with the month of June, and any bed-and-breakfast or inn was going to cost about $1500 for the week.

For the last few years, I had almost always come up with great options, meaning great people and great places, on either craigslist or homeexchange, which was what I needed then for Austin. So I spent several hours one morning in a timeout from packing, renewing our membership and extracting the Berkeley house and its photos from our listing.

Once I was back in and able to operate, I cut and pasted a request for a Maine exchange, simultaneous or nonsimultaneous, on twenty Austin listings (out of ninety on the site). I got a surprising seven positive responses but only one that lined up with the right dates and also had a respondent who followed up the initial back-and-forth. Furthermore, she and her family didn’t need a place to stay in Maine—they had relatives on Mount Desert—but they were willing to let us stay in their extra room. I still sought the ritual of a trade, and that turned out to be the informal “potlatch” of books and peaches.

They are a couple in the general age range of our kids with a daughter exactly the age of our oldest grandson, Leo. I won’t use their names in this blog in order to keep bystanders and civilians anonymous. The connection may have been completely random but, once we got there and began talking, we discovered that we had met the guy’s father and stepmother at a brunch the previous fall on Mount Desert, at the house of Bob Gallon, a forensic psychologist that North Atlantic is publishing. Gallon and our host’s father teach together at the senior college.

Later we discovered another connection—that, as a graduate-student architect, our host had gone to see a close associate of ours, alternative technologist and biochemist John Todd, in Burlington, Vermont, where John now teaches. Though he hadn’t hooked up with John directly, he did see one of his living machines on the roof of a local building.

I had taught with John at Goddard in the mid-seventies, and then we packaged one of his and his wife Nancy’s books for Sierra Club; we later republished it under North Atlantic. John was on the North Atlantic nonprofit board for many years, and he employed our son Robin on Cape Cod for two summers building alternative sewer systems (Robin is now a forty-five-year-old historical geographer and environmental biologist at the San Francisco Estuary Institute). So we and our new friends logged in at well under six degrees of separation.

The eight-year-old was ready for us; she handed out gift necklaces she had made and insisted on helping carry in our things, though most were on the heavy side for her. Then she showed us around the house while introducing us to the three resident cats, the oldest of which, Dante, spends most of his time sauntering between the Scratch Lounge and a mostly collapsed cloth dollhouse. On our last day in Austin, Robert, Katey, and Griffin came to visit.

Robert observed the situation and said, “So he’s got two properties and occupies both.”

Our hosts were not only home-exchange partners; they were wonderful company, as we enjoyed their graciousness, hospitality, wry humor, reggae music, lightness, live chickens, vegetable garden, beneath-the-surface guide to Austin, and daily ceremony as a family.

Another offshoot BTW of re-listing on homeexchange.com was that, within an hour, I got a billion-in-one request for a trade with Toronto for our Maine house on exactly the days we are planning to pass through Toronto.

It is very very hot in Austin in July, at least on 2014’s passage—mid to high nineties. It feels like a blast of sauna whenever you leave the air-conditioned indoors; it can be dizzying. The second day our car thermometer, when we left the vehicle parked in the sun, hit 111, and a lot of food inside melted. To me it still feels like New York City many long summers long ago.

The house is located in a creative development east of town called Agave. Most of the homes are uniquely designed and then crafted for a modern, modular Santa Fe look, plenty of rare adobe colors (purples, mauves, browns, lavenders), creative placement of glass, stacked box-like sections, and unusual angles, also with houses and lots not at right angles to each other. The whole scenario overlooks the city from the eastern hills. Planes from the airport cross here low at night.

The first day we followed directions to downtown, which is four to five miles and twenty-five minutes by car. We took MLK (formerly 19th Street and Highway 969) into the city itself. Then we turned left where MLK dead-ends at Lamar. In thirteen blocks we ended up at Lamar and 6th, which is the location of both Bookpeople of Austin and Whole Foods (the flagship store and its corporate offices here). Bookpeople is like the late Cody’s Books of Berkeley, and its survival in situ is symptomatic of the transmigration of souls: Austin can support readers that Berkeley can’t anymore. And its customers are willing to abjure Amazon. Berkeley meanwhile is part of the techie empire, one of many Texas-California paradoxes, given the politics otherwise. Cody’s and Shambhala are long gone. Moe’s barely hangs on.

After lunch at Bookpeople and a food run at Whole Foods, we continued to the Colorado River, found a dubiously legal parking place, and walked on the trail alongside the water. The landscape and air had a Mark Twain tang, as though we had truly left the southwest and were approaching the lush Mississippi.

After our walk, we got lost trying to find the Lauterstein-Conway Massage School on Burnet (a major thoroughfare that our GPS wouldn’t admit was even a street in Austin). We had to ask directions three times, and after trying to apply each explanation of how to go, we seemed somehow only to get farther away. It took three employees at a Holiday Inn, willingly sucked into our plight and debating with each other the best and most understandable route, to finally get us there. Even they changed their advised map twice before setting us on a consensus course. We had left ninety minutes early for a fifteen-minute drive and barely got there in time.

I had never met David. He is a Facebook friend. Plus years, perhaps decades ago, he had submitted a somatics manuscript to North Atlantic that I regretted not accepting. It was eventually published as Deep Tissue Massage by Complementary Medicine Press. We succeeded in meeting him at the school, as agreed, at four, and our connection soon opened to a delightfully improvised afternoon and evening. David is a kindred spirit, sharing many crosscurrents with us, someone we had (in a sense) known all along without knowing. His school is also one of the premier bodywork training centers in the country, and it was an honor to be his guests there. As we sat in his office chatting for a while, my favorite moment was when he described moving to Austin from his native Chicago and first realizing that he could actually live there, “just the way,” he added, “I thought about my wife-to-be after I met her: Can I love this woman? I think I can.”

We would see why later when we left our car at its 111 degrees in the school lot and went with him to his nearby house to meet Julie for dinner. She is both elegant and wickedly wry. I don’t think that Laura Dern is quite the actress to play her, but it’s in the right direction. Like us, she and David are a mildly mixed marriage, mild at least by today’s standards. He is Jewish; she is Protestant (Methodist), while Lindy is Episcopalian, but her mother was raised Methodist. Taller than her spouse, Julie Harper Lauterstein is as Texas as Lindy is Colorado.

Before heading to the house, we had arranged to pay David for a split zero-balancing session at the end of his workday, so we each got a half-hour treatment. Good palpation is as profound and “other” as a dream-state, and this was no exception. David’s art found a dream body wound within the accumulated tension of so much driving and life transformation. Half the time I was in a trance rooted in the skeletal system and obseriving some of my lost alter egos; half the time I was tracking his work and trying to discern skilled techniques.

Much of what we try to do in dreams, likewise in sex, art, prayer, and shamanic journeying, is to seek our unconscious bodies and give them a conscious body too.

After we joined Julie at their house, they took us to dinner at a fancy Mexican restaurant called Fonda San Miguel. It had fountains, spaciousness, high ceilings, and its walls were filled with art like a museum.

Not knowing the source of the meat (as the waiter didn’t either, even after inquiring of the chef), I took Julie’s lead and ordered squash stuffed with goat-cheese/corn gruel. Quite worth it, though she made the point with the waiter that they should know things like where their meat comes from, and that led to our exchanging stories about the topic, e.g., how much of the unit at Abu Ghraib had formerly worked together at the same chicken factory in West Virginia where they spiced their recreational breaks by throwing birds against the walls, mutilating them alive.

Swimming is not in the journal, but we obviously went swimming in Austin

The next morning we made plans to meet Neil and Elizabeth Carman for lunch. North Atlantic authors (Cosmic Cradle: Spiritual Dimensions of Life Before Birth), they had rented the downstairs of our Berkeley house two summers ago when we were in Maine to get out of the Austin heat. We reconnected at a typical (for them) choice, Casa de Luz, the dining area of a spiritual school for all ages near where we had walked along the Colorado the day before. Macrobiotic with a fixed menu, it was not very good (the corncobs were dry and the soup tasteless); it made Potala, the Tibetan macrobiotic fixed-menu place in Berkeley, seem like Chez Panisse by comparison, but it was healthy, and we were there for the company not the food.

Neil and Elizabeth are a little younger than Lindy and me and they have one main topic which they handle at post-graduate level: the communications of souls who have just passed as they talk about the change of worlds as well as the very different communications of souls who are waiting to be born and establishing connections with their desired parents (or trying psychically to find the right family and close the deal). The couple has researched thousands of the latter such incidents, hence their book with us.

On souls maintaining a link after death, they were particularly excited that day by a new book, The Afterlife of Billy Fingers, written by Billy’s sister Annie Kagan (Billy Fingers is her nickname for her so-called bad-boy brother). According to the Carmans, this is the most paradigm-shattering account of a passage beyond death ever, though I wonder if they know the full available oeuvre of nineteenth-century pioneer researcher Frederick Myers.

The main thing about Neil and Elizabeth is that they so firmly and unshakingly (and good-humoredly) believe in a karmic, reincarnational universe that they bring contact recognition with them. In their presence, everything about one’s own life falls into cosmic perspective: this whole Earth journey (with its mini-odysseys, road trips, and labyrinths) becomes part of the greater overall pilgrimage of souls through the universe’s many realities, aspects, frequencies, states of awakening and going back to sleep, and sub-cosmoses across an unknown, profound, and emergent realm that could only be dubbed All That Is.

Neil’s day job is quite a contrast. A chemical botanist by training, he has worked for years for Clean Air Texas and the Texas Sierra Club, mainly to help close down coal plants (nationally but mostly in Texas). He helps fight permits and file lawsuits and prepares testimony for court appearances. In general, he opposes rate increases that would give the plants more operating capital as well as buy off their inefficiencies. “The plants are old technology, dinosaurs,” he told us with the same wide-eyed, ingenuous good humor when discussing the incarnation of souls, as if they and the improvement of the energy grid were calibers of the same sanguine outcome. He noted that just a few years ago it seemed impossible that anti-coal forces would make a dent or close a single plant, plus the Bush administration was proposing 200 new units in a rush to achieve U.S. energy independence. But both the economics and technology had changed breathtakingly fast. Only a few of those 200 were ever built (including one or two in Texas), while 165 plants, thirty-five percent of the entire US coal fleet, had been shut down in that same time. “Coal plants only turn about thirty percent of their output into useable energy,” Neil said; “the rest, seventy percent, is just lost. $85 million worth of coal burned a year now produces less electricity than the same amount of money invested in solar and wind. San Antonio needs about a billion dollars to clean the scrubbers of their Deely coal plant built in the eighties, but they can generate the same amount of electricity from solar for a fraction of that cost.”

When I told Robert Phoenix about this discussion, he asked me if Neil had provided information what happened to the coal-plant workers. “No, he didn’t. I imagine that there are a lot of individual stories and outcomes.”

Robert rejoined, “I’m betting that, for every coal plant shut down, three of four meth labs spring up.”

When I presented this exchange to our Austin host, he said, “More likely they’re fracking or working natural gas.”

When I passed all this cumulative banter on to Neil, he differed, “No, that’s part of the negotiation. Some get retirement with severance pay; some get re-trained; it’s not perfect, but it’s not like they suddenly close the plant and kick the employees out on the street. They can’t do that.”

Robert (BTW) told some good fracking stories—I mean there are no good fracking stories, but they’re ghoulishly engaging, like companies convincing families to have water carted in for their drinking pleasure so that their engineers can turn the local supply into industrial use only. Then there was the friendly guy at a Jim’s who told Bob he’s had a wife with Alzheimers at home and an oil well in West Texas that earns him just as much by selling the water around it for fracking. “I admired the guy until I realized he was an oilman. ‘I guess I am,’ he said when I put the question to him.”

Barton Springs, mythologized in a Slaid Cleaves song (“New Year’s Day”), was close to our lunch site, so Lindy and I planned to go swimming there afterwards. Neil was quick with not just directions but a lot of information: “Sixty-eight degrees year-round, the length of two football fields, huge aquifers under Austin of which Barton is a major vent, a million gallons of fresh water per minute….” However, what he didn’t know was that the pool is closed on Thursdays for cleaning, so we joined a host of other disappointed folks, many of them tourists, staring in from outside the gates. A good number of locals, however, were swimming beyond the legal boundaries in the outflow. I still find a million gallons per minute hard to fathom. Lindy and I wavered on whether to join the illegal swimmers but finally decided to leave Barton for the next day.

One thing I have mused about all along and that also drew us to allot six days to Austin: how so many people who have never been here speak of it as an oasis in Texas. Now I don’t think that that’s quite accurate except that the area is literally an underground sea. Texas itself is both awakening and alive and Austin is hopefully the harbinger and external manifestation of something much larger.

In the evening we and our hosts went out to dinner at Hillside Farmacy and then together to hear Slaid Cleaves perform at the Cactus Café on the University of Texas campus. Lindy and I have been listening to Slaid since he did a homecoming concert at the Grand in Ellsworth, Maine, in 2002. A songwriter/folksinger on the Portland and southern Maine circuit in his earlier youth, he had moved to Austin to apprentice at the roots of his sound a few years before the homecoming. Even then (at the Grand) he was as much Texas as Maine: blended landscapes, politics, and chords, plus all-out Texas yodeling. By now he had become an Austin mainstay, packing a sold-out lounge space of about 100 on his farewell night before departing on three months of U.S. and international touring.

Slaid is good enough to have not only a loyal local following but pretty much fill venues across the U.S. and Europe every year. He is either playing in Austin or touring most of the time. He is also good enough that he ought to have become more famous than he is. In our winner-take-all society I think of him as perhaps the best unknown songwriter/country-and-western singer going, if you take into account both the quality of his work and its relative degree of obscurity.

Slaid’s language is fresh and politically astute at subtle levels; he mixes words and melodies effortlessly, and he has a natural feeling for the depth of human longing, loss, and pain. He also has an authentic warble or twang that descends into the soul: a mysterious combination of song and voice that, each in his or her own way, marks the greats: Sinatra, Jo Stafford, Bob Dylan, Al Jolson, Sarah Vaughn, Bobby Darin, Willie Nelson. I am not saying that Slaid resembles any of them. I am saying that he does more than pen and croon country and western ballads. He puts his heart and full being into the songs, and people hear that, recognize the authenticity, and want to be around it. You can check his out lyrics online or watch him play on YouTube. For instance: “On a corner, trembling in the wind/Amazed at the mess they’re in” or “You’ll never see those blue skies/through young eyes again.” Or a recent gospel: “It ain’t the silver, It ain’t the bronze / It doesn’t matter, Whose team you’re on / No precious metal, Will save your soul

/ But if you seek glory, Go for the gold.”

With graying hair now at fifty, Slaid has reached his prime, and the audience knows it and responds accordingly, lots of repartee and encores, including unplugging the mikes for the last number and going among the audience. He played two great sets July 10th with local guitarist Scrappy Judd Newcomb. Both of them walked the crowd for the final number.

It was gratifying to get to see Slaid on his home turf, as we told him between sets when he went outside to mingle. He knew about our long road trip from my emails, and he offered to sing one—only one—of three songs I requested: Oh Roberta, which is not by him but his protégé Graham Weber. Great song: “Used to think I was something, / I’m still something I suppose” and “I’m here clear left of center on the unridable road, / Wish I knew the way / that I was ’sposed to go, / But I’m still the same old fool you used to know. / Oh Roberta, where have you gone?”

Slaid introduced the song with the following repartee with Scrappy. “This is for our friends Richard and Lindy who are stopping by tonight on their road trip from Berkeley, California, to Portland, Maine.”

Scrappy: “That’s far.”

Slaid: “Farther even than we’re going on tour, buddy.”

A back story of the evening was that I misread the email from our hosts and thought that they had reserved seats for all four of us, whereas they thought that we already had our own seats. Since the show was sold out, Lindy and I spent an anxious forty-five minutes mingling at the door, trying to get a note to Slaid. I even did a psychic exercise to help salvage things, while our new friends were offering to sell us their tickets and go elsewhere. None of that was necessary (well maybe the exercise helped). The ticket taker, when she finally appeared in front of the line, heard Lindy’s explanation and lament and waved off her note to Slaid. She sold us two tickets on the spot and then sent us in at the front of a long line made up of those who already had purchased tickets. We were the first ones in the room and saved four seats in the second row.

Once Lindy and I prioritized Barton Springs early the next afternoon, Neil and Elizabeth decided to meet us there. 95-degree air and 68-degree water were an ideal combination. The fresh-running spring, whether it actually delivers a full million gallons per minute, eliminates the necessity for chlorine and keeps its water clean. In fact Barton is really a large pond with native salamanders in its reeds and the mud below. Posted signs warn you not to disturb their habitat.

The scene was reminiscent of many a bathing site from my life (Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, hotel pools, Vermont glacial ponds, and Maine and New York State lakes). Only a dollar each for us to get in as seniors, followed by an open-air changing room, which relieved some of the funereal quality of an all-ages dressing zone. Walls alone protected privacy.

Barton’s water is quite alive and charged, homeopathic no doubt, not as cold as Maine lakes but plenty startling. I felt a transformation as well as a healing crisis from the core on out, especially swimming underwater with my eyes open: a murky underworld.

I went in three separate times and in between lay on the grass under the trees with Lindy and our friends. As Rudolf Steiner (among others) has pointed out, water brings in astral energy and fills this plane with a mystical, joyful energy, pretty much wherever it is (bar of course a ship in a storm at sea or a hurricane hitting land).

We had to hurry back to the house to get ready for watching Dave Insley play solo at the grill of the Driskill Hotel in downtown Austin—a 6-8 stint at which we were also meeting an unknown, distant relative of my generation from my mother’s father’s side of the family. Since I never met my genetic father and know nothing of his lineage, my mother’s mother’s family is the only blood genealogy I have had. But Ellen Rothkrug gave me a family tree by email, the first I ever had of my mother’s father’s line. Our shared ancestor was our great-great-grandfather Ezra. Ellen’s line was via Ezra’s son Abraham, as were the only other Rothkrugs I had met other than my mother and her brothers and their families: a cluster in Great Neck, New York. We, on the other hand, came through Ezra’s son Nathan.

Ellen’s father had moved from Brooklyn to Amarillo, decided to be no longer Jewish in response to the Holocaust, married a Catholic, then raised his kids Catholic and Texan. Ellen was so Texan in fact that she had promised to bring along her friends Willie Nelson’s granddaughter and Kinky Friedman (of the mystery novels like Elvis, Jesus, and Coca Cola and Kill Two Birds & Get Stoned, and the music group “Kinky Friedman and the Texas Jewboys”), but when she arrived at the Driskill with only an old college friend, she said that Kinky wasn’t answering his phone and Willie’s granddaughter was too busy. It’s a wonder she didn’t offer to bring her other friend, politician Wendy Davis.

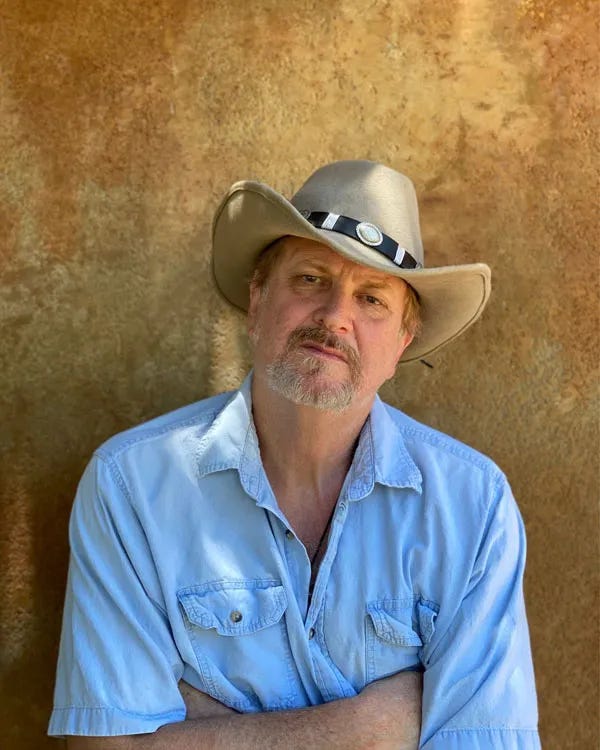

I felt bad for Dave. It can’t be fun playing for people who are sitting around clinking cocktail glasses, chatting, telling jokes, ordering again from the bar, and not listening or even noticing the guy in the cowboy hat stroking a guitar at a mike. But Dave said that he likes the gig, only a few blocks walk from his house, so he plays it often. He did mostly covers in the first set: Merle Haggard, Statler Brothers, Johnny Mercer, Willie Nelson.

Before the set, he greeted Lindy and me enthusiastically. After being introduced to his songs on WERU in Maine about nine years ago, we had gone to hear him and his band The Careless Smokers at a brewery in Santa Rosa (the tour dates and venues were on his website). The following year, North Atlantic had enough of a profit to do philanthropy, and we gave $5000 to WERU to invite him and the band to the station’s Full Circle Fair in Blue Hill. That turned us and Dave into friends and got us hanging out together a bit in Maine. We hadn’t seen him since, till he came in with his big Stetson July 11th and gave us a hug.

It wasn’t entirely comfortable visiting with Ellen and her friend, too much small-talk and endless over-amped conversation. After a while it was one or the other so, without any more in common between us than 1/32nd DNA, I separated for the second set and went to the bar to focus on Dave. Lindy soon joined me, promising Ellen we’d reconnect afterward.

Mr. Insley is a good songwriter himself, funny and soulful and, after we got into the vicinity, he played a lot of his own stuff for us, including his masterpiece Other Trails to Ride. “I don’t do this for just anyone, you know,” he whispered.

Here’s what I wrote about it a few years ago:

Consider these lines from "Other Trails to Ride"; it starts: "Put me on my favorite pony / Point us toward the settin' sun. / Please make sure my hat's tipped right / And there's bullets in my gun....” Then: "Give my weary mind a rest and let my spirit sleep.” This death song only gets more awesome: "When this ol' paint comes back alone / Give him oats and give him hay./ Brush him down and turn him out/and put my tack away."

Step aside; the man is on a song-writing roll: "Know how much I loved the road that I’ve been down with you / and all them pretty sunflowers and all the hard miles too... and "I loved you in your waking hours, / Now I'll love you in your dreams."

Then he tosses out the magic invocation, the hope and wish, the terror and haunting too, for life on Earth since the Ice Age shaman found the planetary mind inside himself and peered into the darkness, from where he heard an answer coming back that we still hear, listen or not: “Even though you can’t see me, / I’m still here by your side.”

After the show, Ellen took pictures of Lindy and me on the steps of the Driskill.

It is a fancy piece of the old West, and the gauntlet from there there to where we parked our car a few block away was like a honkytonk version of North Beach: girls in bikinis and hot pants alongside aggressively confrontative and bored, goofy barkers trying to lure in tourists, even getting in your face with their antics if you try to slip by (Lindy played along because she’s good at that, but I’m not and didn’t, so she teased me too, making for a double whammy), loud bands overlapping in the night air, a new one coming in from a rooftop stage as a prior one begins to fade from ground level, then repeats of the sequence. “That’s why it’s called ‘Dirty Sixth,’” our host explained later “the part of Sixth Street you were on.”

Lots of great ideas but limited energy to enact them all, so the next day, Saturday, we focused on the Blanton Art Museum at the University of Texas. It is hard to say much about a random part of collection viewed in a museum in this type of narrative. Either you say a whole lot about the specific works, singling out key pieces or you check the “art museum, generic” box and move on. I’ll describe a few pieces that deepened my perspective.

First of all, what stood out as special was the border art by, no surprise, El Paso artists: a statue of a “coyote” carrying a woman across the Rio Grande, the figures coated in automobile-chrome colors; likewise a sculpture of a rodeo event, the bull and cowboy both with demonic lamp-lit eyes, other smaller figures below (like an owl and captive rabbit) extending the rodeo theme into a general statement about predator and prey in nation and border and relations.

What mostly struck me about the museum was context—how much you are always looking at that more than content—more than individual works. First of all, there is the context that puts an image or object in an aesthetic setting of one sort or another, which applies to every object in a museum in some way or other. Then (nowadays) conceptual art is mixed with old-fashioned representational art at almost every major venue, and the two open sets overlap without any sort of disclaimer about their miscegenation. That is the second context, the way in which every piece of art puts the art around it into a different context. In that regard, I took a picture from inside a room of Greek sculptures of Lindy looking at modern expressionist art in an adjacent room. Elsewhere Peruvian whistling jugs morphed into Renaissance representations of Mary and Jesus and the Crucifixion and Beatification, the other way into North American Indian artifacts, sculptures built out of Nigerian beer-can metal, and a continuously running loop of a Korean woman listening to and then mimicking, I think it was Lightning Hopkins, as what he was singing about, lady-lover ghosts, got turned into some sort of occult Korean dirge. Since all of this stuff gets integrated in one’s brain and imagination at the same time, the various pieces form a collective background for each other and frame their meanings.

Then there is the context of their all being in a University of Texas art museum and what that says about the flow of meanings in modernity.

Three other things: it struck me, while looking at Italian representations of God, Jesus, and Mary, that the fundamentalist, holy-roller notion of God as a wise or stern old man is deeply imbedded culturally. The projection of other wise or stern old men onto the space that God supposedly occupies outside of ordinary time and space drives authoritarian and punitive belief systems and religious self-righteousness. It is not as though God for them is ever a swirling alphabet or genderless beam of light. They behave as though he was always a gringo judge on a Divine Supreme Court, and that’s how the mainstream Renaissance saw him too.

Caesar Augustus in his rendering by an anonymous Roman sculptor is modern and empathic enough to be a Western Buddha or Thomas Jefferson, and he underlies images invoked by Charles Olson in his poem “The Distances,” a mystery trope I memorized and iconicized back in college. Now I saw “old Caesar” and “young Augustus” in another medium and thought about my passage through life from the age of Augustus back when I first read the poem in high school to the age of Caesar now. I am ten years older than Olson himself, our patriarch, when he died.

A lot of modern art, even going back into the mid-twentieth century, is made up of parts of hyperobjects in the sense that Timothy Morton (whom we will meet in a few days) uses the term. That is, the artist presents only the portion of a much greater reality that he can grasp or access, but the portion is constructed in such a way as to cue its meaning contained in an unseen reality which in itself is more massively distributed in time and space, yet also viscous enough to stick to every onlooker, especially in ways that it doesn’t exist materially, ways that are primarily unconscious. In the Blanton, two works of a Persian woman’s op-art-like paintings were especially hyperobjective, having no meaning except to jar one’s visual optics, optical cortex, and brain into a state of axiomatic uncertainty.

Hard to believe, but we missed Dave Insley and the Careless Smokers at the White Horse. It came from trying to get dinner at the Thai Fresh restaurant before his concert, which was 7:30 to 9:00. We started too late, got lost looking for the restaurant, then had to double-back on the I35 access road, plus we had to wait a very long time for the food.

However while headed toward Thai Fresh, crossing over the Colorado River on the Congress Street Bridge, Lindy remembered that the bats come out there at sunset, a much-celebrated nightly event. Pretty certain by then that we would not finish eating in time for the concert, we calculated that we might well be re-crossing the bridge at the bat’s hour. In fact, we were approaching it at 8:20—July 12th sunset in Austin (according to the cell phone) was 8:35:09. As we reached the bridge, Lindy caught on faster than me that this was no incidental deal and the milling crowds were for something big. People were gathering in droves for the event, and they were parking in the Austin American Statesman lot right before the bridge. You see, I misread a sign and thought that they were gathering and parking for a high-school performance of Oklahoma! By the time I understood, I had passed the entrance and was headed over the bridge. I had to turn around on a dead-end side-street at the river and then double-back, a time-consuming event that took us almost to sunset.

A security guard was waving cars in to the Austin American—it was all on the up and up; another was helping people park as if it were a sporting event, and there was no charge. Then we joined in a football- or baseball-like throng leaving our respective cars. The crowd divided. A cadre of people headed right for the bridge; others got themselves seated on a small grass knoll facing the bridge foundation on the southeast side under an Austin American Statesman Bats banner, probably about 150 there, many with cell phone lenses raised expectantly or movie cameras on tripods.

The river itself was filled with waiting boats, kayaks, and even a large ferry. Up above, the pedestrian walkway of the near side of the bridge was packed too and, just as we were trying to decide whether to go for the meadow or the bridge, a spot opened up in the upper crowd and we went for it: the bridge.

You had to wonder if the bats would perform on schedule or if they were even perhaps intimidated by the mob. If this happened every night, perhaps they were inured by now.

Time passed, and nothing happened; yet the crowd seemed undeterred and anticipatory, as though the appearance was inevitable. Those bats were going to come out, no matter.

It was about fifteen minutes past sunset when the first creatures appeared—the unmistakably erratic flying-mammal dance in twilight. After that, it was batmania. They came from under the bridge in such great numbers and moving so rapidly that it was like looking at a moiré pattern rather than individual animals. The exodus was hard to see, let alone photograph in dusk, though flash bulbs were going off everywhere. The wave became a swarm, angling over the river and then traveling in the fading light behind buildings on the horizon, looking like successive swarms of mosquitos. Every time I looked under the bridge, the wave of emerging bats was still undulating, which meant hundreds more per second were emerging. Every time I turned to the far-off buildings, I saw ebbing and waning phases of a heliacal swarm diffusing into the city, ostensibly to hunt the by-ways by night. No, they were hardly intimidated. They might have even enjoyed the audience in their way, a sort of fellow-mammal confirmation of their way of life and nocturnal motif.

I can’t tell you how many bats emerged overall: certainly thousands, probably tens or hundreds of thousands; it hardly matters. It was the human mirroring of the event that stands out.

I think that it says something, not unrelated to the art museum but much more powerful, that this many people wanted to see bats emerge at dusk—a natural event masking an alien intelligence behind it. After all, it wasn’t Batman they were gathered for or looking at; it was bats themselves, though maybe the two have a prior interreferentiality, as if to say, “I know that we won’t see Batman, but maybe bats are his original force-field and closer to my heart anyway.”

The need to have the natural world mean something, to speak to us, to have the unseen real make itself visible in its proximal aspects, to display as the dark goddess and the pagan veil, is profound and unquenchable enough. For all the superheroes and video games and sporting events and guns, here was something spiritually and nakedly inspirational: a cross-section of the secular populace acknowledging the indelible meaning and essential beauty and mystery of another mind. Coming out of a cultural artifact adapted for their prehuman ritual, the bats redefined space itself with their bodies and hard-wired skills, redefined life and what it means to be here on this planet and express their body-minds. Meanwhile the gathering said that humans are not too far gone during this phase of their video-game, virtual-reality, cash-and-carry commodity obsessions and accompanying mega-extinction of the Earth’s biology to appreciate the planet and the gods of nature, at a vestigial level. It doesn’t help much, but it doesn’t hurt either. It’s a bit of payback for civilization’s worth of betrayal but at least that.

The transmigration of souls in Texas indeed!

Houston

The Houston freeways and toll roads are fast-moving and more complex, challenging, and terrifying than the LA freeways. People seem to believe in their bubbles more fervidly. One keeps getting confronted with having to move over a lane to the left so to not be in an exit lane, while other drivers, pedaling at 70+ will not let you in, on principle. It’s routinely a lane shift and a prayer. Drivers pass on the right at startlingly high speed, everywhere and without warning or concern, even where there isn’t a lane. Markers to tell you what lane to be in for what road and shift are painted on the pavement in front rather than on long-view signage above. And there are many local lane-permission euphemisms about fast-trak, HOV only (High Occupancy Vehicles) not immediately obvious to us). It adds up deficits in the nervous system until you are exhausted and want to scream, “Let me out of this road-rage nightmare?”

What is notable about Texas in general is new construction everywhere. No depression or recession or stagnation here, no sulking while blaming Obama. They can’t build stuff fast enough. Cranes, cranes, cranes, like landers from War of the Worlds. And Houston’s vast medical complex with its idiosyncratically and exotically architected skyscrapers, some circular and webbed, is really a city within a city; it looks like the skyline from a planet circling Alpha Centauri.

Rick Perry may be a lackey for the bosses, but when he sells Texas abroad, say in JBrown’s California, he’s got a legitimate tailwind and serious financial backup. Even rads like Robert Phoenix admit that California is a hopeless tangle of maddening regulations and red tape for them. Can you imagine what it’s like for a big-footprint corporation?

In El Paso, people either locked their doors or (more often) didn’t when leaving their houses for a spell. No big deal either way. As Bobby pointed out, each block is a small community and much of its life takes place on the street, so neighborhood watch is implicit and fundamental, like who is that dude wandering through the barbecue?

In Houston it’s the opposite. Everyone is locking their door and sometimes a double-door as if it were Baghdad and the Sunni invaders could be here any second. You don’t go in the backyard without making sure that at least one of the front doors even has a bolt in place. And I am speaking about autopilot rather than actual concern. No one really expects trouble; it’s a habit and a mood. It was explained to me that this precaution has a lot, but not everything, to do with the 250,000 refugees from New Orleans and Katrina (with Louisiana morals and chutzpah) that this city had to absorb in about a week: school system, social services, hospitals, jails. Home invasion robberies are common. It has been both hinted at and confided to me that the rogues are all black people who have no manners, ethics, or scruples, pure L’siana. This may or may not be the case, I mean the prevalence of the myth; I am just sharing hearsay. If these dudes want the contents of an ATM, say, they steal a pickup, park a block away, tie a chain to the machine, pull it out of the wall with their stolen vehicle, leaving behind debris and collateral damage to the structure (and, later, the stolen pickup). They put the ATM and accompanying chain and cement in their own car for later deconstruction, and leave the scene. Louisiana kids are two to four grades behind their age level and consistently turn down their school lunches with lines like, “We don’t eat this shit.” When told that his Katrina benefits might be cut off, one half-smiling, unabashed chap told a reporter, “If they cut my benefits, I’m gonna have to get my hustle back on.”

I won’t cite my sources, but this was fairly common scuttlebutt.

Of course I experienced none of it directly, only the apocalyptic travel corridor, generating fender benders, stalled trucks, and ambulances. Not an epidemic by any means but a steady enough algorithm to let you know people are driving too fast in their abstracted air-conditioned bubbles.

It was a 162.2 miles from our Austin hosts’ front door to the front door of our friends in Charlestown Colony, Bear Creek, suburban Houston, and that includes a spell of getting lost after Interstate 10. We detoured farther south to Houston (instead heading through Dallas, the more direct route to Maine); we did so for very different reasons because it was really out of our way and we faced a huge haul north.

First, we wanted to meet two authors, who are professors at Rice University, Jeffrey Kripal and Timothy Morton. Second, we wanted to visit Bill and Paula Blakeslee.

These have disparate back stories. Bill worked in the convention department of Grossinger’s, my father’s hotel, in the late seventies when we visited regularly from Vermont and (once) from California. He is thirteen years younger than us and back then was a man in his early twenties at his first gig (out of Elmira-Corning, New York, by way of a job fair at his college, SUNY at Delhi, hired before he even graduated, initially to do kitchen preparation, but he later persuaded them that he was management material). That was when Lindy met him while she was using my stepmother’s office in which to write during our visits there. Their conjunction created a bit of an anima-animus thing; she wrote a short story about it and him, gave it to him, and also signed and gifted a book of her poems. Approximately thirty years passed since then. We moved to California, and Grossinger’s went out of business. It was a big surprise when, in the mid aughts, Bill tracked Lindy down online and told her how he had reread and valued those poems of hers over the years. In 2008 he came to the Bay Area with his wife Paula and visited with us in Berkeley.

We don’t share a large intellectual realm, but we had enough of an overlapping sector of American pop culture for conversation, plus Lindy intuitively connects to people. Bill is, to work an overworked cliché, the nicest guy in the world—gracious, generous, receptive, open-minded, thoughtful not just at random moments but as a general practice. If anyone is inconvenienced or he gets in their way, he apologizes with credible sincerity even if the misstep it’s not his doing. He treats his employees royally like family. He will even drive a worker lacking a vehicle to his or her home at the end of the day. He still plays pick-up basketball with much younger guys. One of his favorite comments is “There you go!” That’s a nice guy’s signature phrase; the kindness is in the blood.

He told us that his father once said to him, “‘You bring me gifts, fill my car with gas, wash it, vacuum it, leave me beer, mow my lawn, do the edging with the clippers. You are a decent kid. Your brothers drink my beer, eat my food, use up the gas in my car, leave a mess, and then ask for money to get them home.’ And I didn’t solicit that from Dad. He just said it.”

Bill runs Del Vecchio Foods, which is—there is no other way to put it—a sausage factory. It is located in the Chinatown/Japantown district of Houston, when street signs are, I think, both Japanese and Chinese as well as English.

You might wonder (but probably not) how, in this bizarre samsara, one goes from the Tree of Life to a sausage factory in the same pilgrimage within the a labyrinth, but really, when you come right down to it, aren’t they both part of the same connected reality along with Juarez, Slaid Cleaves at the Cactus Café, the Scratch Lounge, and bats at twilight? I don’t think that the slaughtering and grinding up of pigs, decidedly non-range-fed pigs from Oklahoma, to fashion a variety of “all-natural” sausages is a wonderful thing in itself, but it is on the same vibration as all the rest of what is happening: the roads that got us here, the petrol products that make Texas Texas and the West the West, the vast infrastructure beneath “Messages from the Afterlife,” Tree of Life, Billy Fingers, the El Paso zendo. There’s no good and bad, right and wrong, as such at our level. We don’t suddenly leave the sacred for the secular or vice versa. This is all one phase, one big bell ringing in a one big spacious sky, generating one reality, for the Dalai Lama and al Qaeda both. All this stuff we are encountering, from Tree of Life to Del Vecchio Sausage, are somewhere in the vast American upper-middle-class middle ground and Planet Earth’s physical-plane vibration.

When we got our tour of Del Vecchio’s Foods, what I saw were men in honest well-paid employment, supporting families, collaborating in a very cold room with good spirit and camaraderie, a bounce and spring in their step and repartee. That doesn’t help the pigs much, but you can’t cover every base, let alone all of them at the same time. There are plenty of other victims on the road from to civilization and prosperity, from the birth of the symbol through the migration of sentient beings into modernity.

Who was Del Vecchio to Blakeslee? Well, after Bill left Grossinger’s in 1979, he and his Elmira-Corning buddies discovered that there was no suitable work in New York State, so they migrated en masse to Houston (for mutual support and to keep their community intact). Bill met Paula while working food management for Exxon Chemical where she was an executive secretary to a vice-president.

Frank Vecchio (Del an ornamental preposition—“of” in Italian and Spanish) was Bill’s neighbor in Elmira (actually Big Flats, between Corning and Elmira); he followed the crew to Houston a few years later. First, he tried industrial food service but didn’t like the bureaucracy and unforgiving in-step regimentation, so he proposed to the boys tackling something risky and entrepreneurial: “I can’t pay you much, but at least it will be ours.” He started the sausage factory in partnership with Bill but died of a heart attack two years later. Bill was heart-broken—he loved the guy, had known him since he was a teenager—so he bought out his widow and has been running the factory since.

Frank’s ashes rest in a case in the main office, though there aren’t many of them left despite that he was a full-sized man because thieves broke in and stole, among other things, the urn, spilling what didn’t leave with it. What’s on the shelf had to be salvaged from the desk and floor.

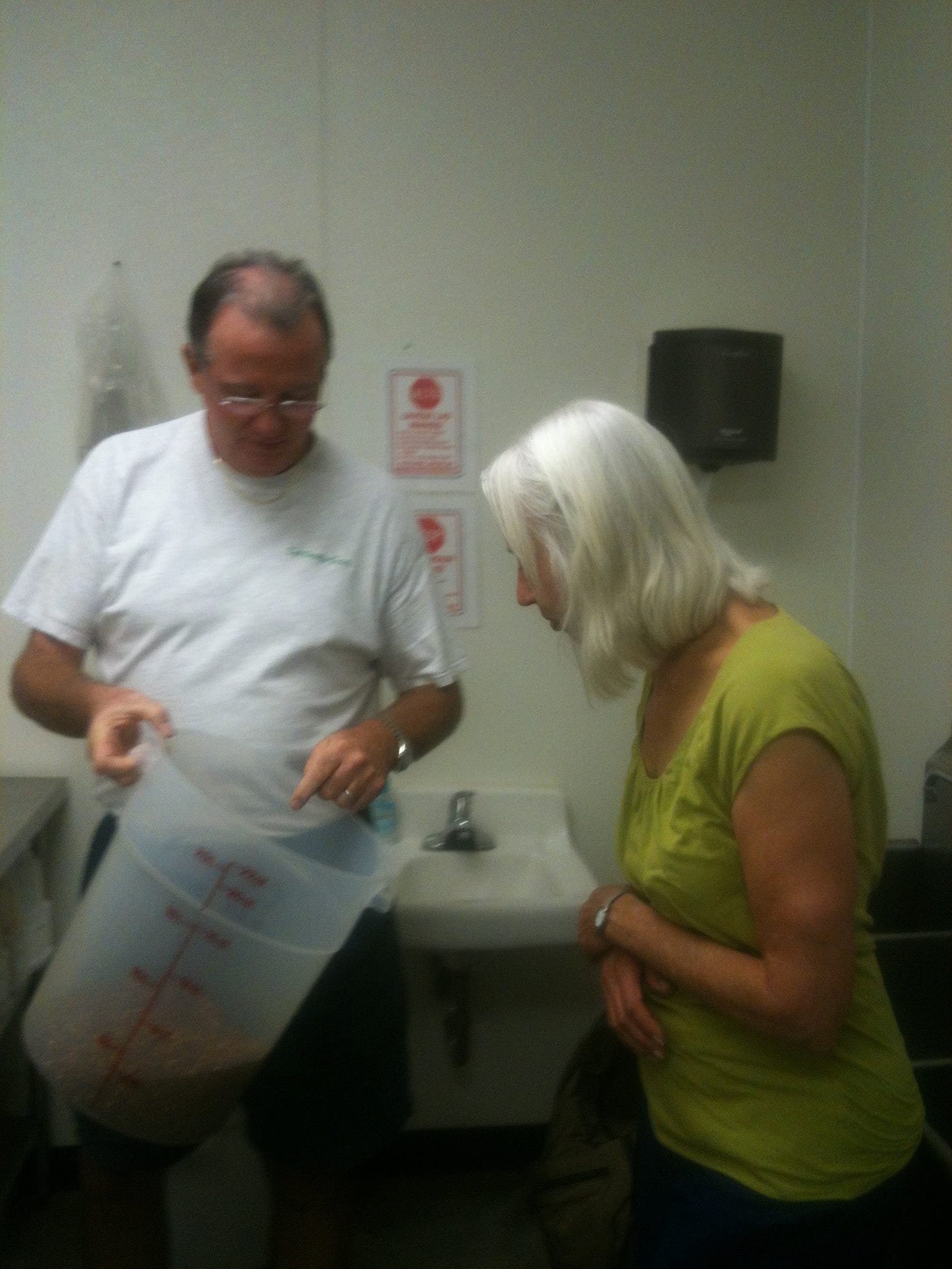

In my sharing photos of Del Vecchio’s, you can see Bill, Lindy, and me dressed to enter the action zone, Lindy sniffing the oregano as Bill holds it out (very sweet in that quantity), then the men shaping raw materials into products on order.

The place is mainly about maintaining absolute coldness, keeping scrupulous records, and providing the little things that Government inspectors look for. The USDA even has its own desk and small office because someone from the agency is there all the time. Every movement of every batch of meat, whether sausaged yet or still raw ingredients, has to be tracked and catalogued. In fact, there are computer chips that retain the high and low experienced by every shipment of sausage and in every storage batch. In that context, there is a large -4 degrees storage chamber, a temperature that has become the industry standard in a very competitive business. You are selling negative degrees; it’s a big “extra,” a valuable commodity, Bill explains. Zero-degree trucks make up the company fleet.

Del Vecchio’s varieties of sausages are used in restaurants locally but travel as far as Boston and Washington State and are about to debut in Mexico City once the NAFTA-related paperwork is completed. This fare includes English bangers, classic Italian sausage, Argentinian style sausage (Bill’s bestseller, using the herb Aji Molito imported from Argentina), Cajun sausage, bratwurst, and pork ducken dressing.

The gist of the factory (again) is paperwork, as if a continuous scientific experiment were being conducted, except the experiment is life: a lot of ground-up pig (and some chicken, turkey, and duck). This fact has to be overlooked in order to maintain sanity, for employees too I think, but which of course registers karmically in the overall picture, meaning not on Bill’s conscience per se but all of ours, all of us who are in the game and surviving by consuming the metabolic and etheric energy of other life forms. As an Eskimo sage puts it:

“The greatest peril in life lies in the fact that human food consists entirely of souls. All the creatures that we have to kill and eat, all those that we have to strike down and destroy to make clothes for ourselves, have souls like we do, souls that do not perish with the body, and which therefore must be propitiated lest they should revenge themselves on us for taking away their bodies.”

On our first full day in Houston, Paula ferried us to Del Vecchio’s for the full tour, then into the museum district. This was air-conditioned bubble-driving at its best, 70 mph, lots of sudden braking, with the car in front of almost bumper to bumper. When Paula changed lanes, she just did, letting the pieces fall. She liked to say to no one in particular (and without looking), “Thank you for being a gentleman,” or “Thank you, ma’am,” when the reality was usually the opposite.

We were ostensibly getting a taste of downtown, but we never saw anything like a New-York-style or even San Francisco urban cluster. Houston is a very spread-out place. In our three days there, Lindy and I took three ordinary downtown trips, and it amounted to more than 150 miles. It’s usual to go thirty miles to shop or see friends on a combination of 10, 610, 59, and other roads.

That day we ultimately opted for the Asia Society Museum and Restaurant as our best option. That reminds me of another Texas thing: fairly fancy restaurants without waiters or waitresses (Thai Fresh in Austin, for instance, or Swad, the Hari Krishna Indian place where we went with Neil and Elizabeth our last night). You order at the cash register; they stick a number on your table, and then the food arrives. Add the Austin Art Museum, the Asia Society, and, later, Rice University to the list. Yeah, I know it’s common otherwise too, but it’s more startling at upscale places.

It was not easy finding the Asia Society, and we saw a lot of that part of downtown Houston in the process, also got in some high-heat-and-humidity walking. (There was however a brief torrential thunderstorm just after we arrived the day before, even continuing after the sun came back out brightly shining, a quickly disappearing stream in the street.) I was particularly taken with the trolley—I tend like idiosyncratic public transports like the gondola linking upper and lower Quebec City. Houston has a major trolley line, so I took a picture of it and almost got run over. Lindy and I also had a bad moment when we mindlessly followed Paula into a street against a red light and encountered a stampede of cars. We had stopped thinking for ourselves; we went when she did.

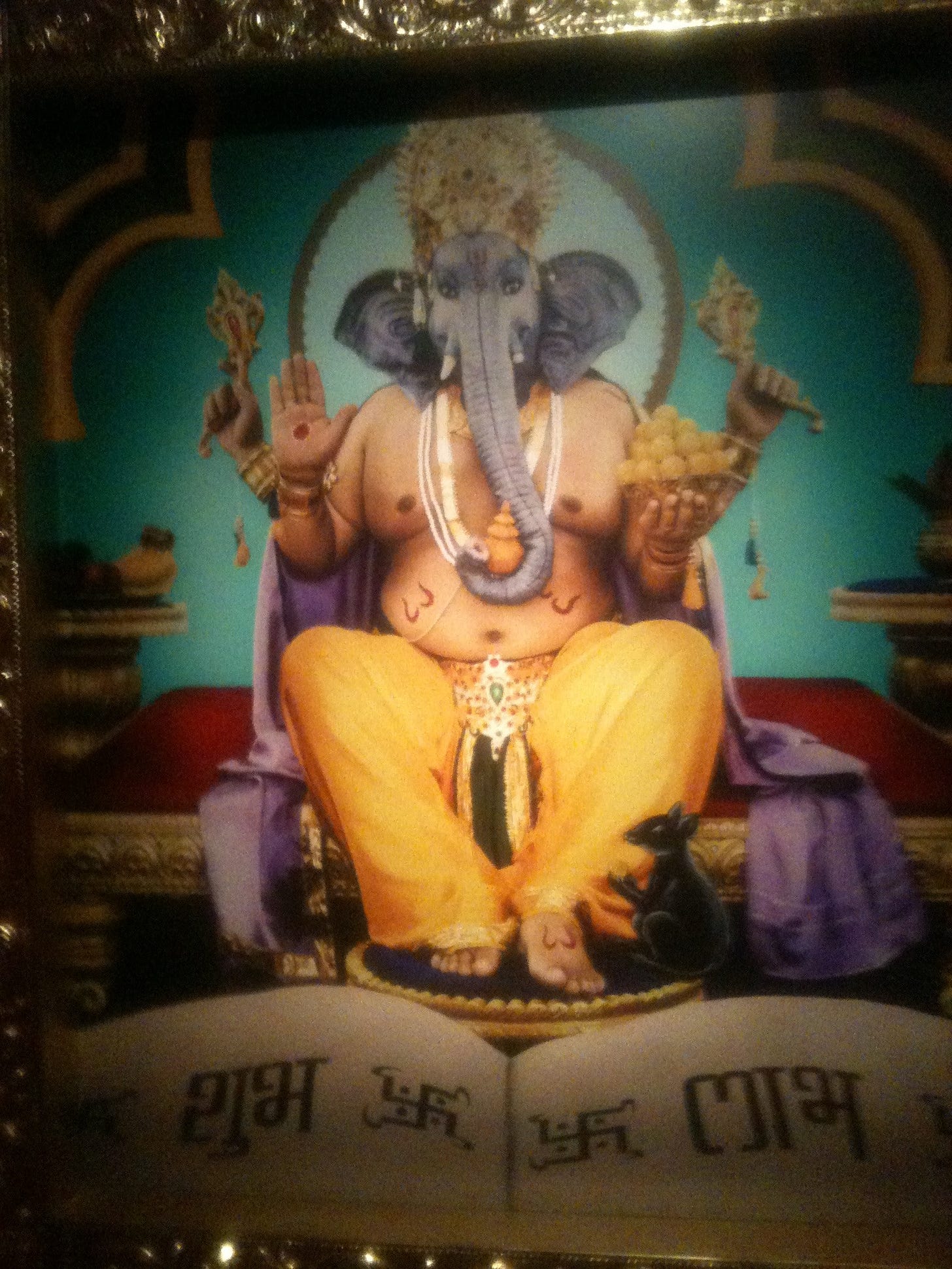

The Asia Society featured a large, carefully curated exhibit entitled “Gods of India.” As we entered, a bunch of exuberant Indian school children and their chaperones were exiting in much disarray and bickering among them, especially across age gaps, grandmothers with their saris and jeweled faces shooing along veering tots.

The exhibit consisted of three versions of gods like Ganesh, Kali, Shiva, Brahma, Lakshmi, and crew. The first was classic old paintings. The second was chromolithography on heavy paper with glitter. The third was giant modern photographs of Indian media stars (but also a stewardess and a CNBC anchor who became famous for appearing in these very photographs) posing amid much paraphernalia and costuming as each of the gods. A bulletin board and post-its were provided for comments, and the kids we had just seen had participated. My favorite was Sameer’s: “I love the gods so much.” Many of the others proposed about the same, just not as superbly.

We hung out with Jeff and Tim for dinner that night and then on the Rice campus the next morning through lunch. Our dinner group included Jeff, Tim, their wives (both of which Lindy and I remember vividly but, unfortunately, namelessly), and Tim’s children, Claire (12, I think) and Simon (5). This girl and boy were more than patient; they were beatific, charming, articulate, elegant (they do brief daily meditation practice, a gentle training that no doubt helps). When we got together on the Rice Campus, they came along because it was, as Tim said, it was “Camp Daddy” day. The wives weren’t present for that (except Lindy).

During the two events we had a riveting, hilarious, also gritty running conversation that would be impossible to reproduce without notes. I would mainly like to herald and recommend both these guys’ works. Different from each other as they are, they are at the vanguard of an unnamed, post-deconstructionist new wave of academic (really anti-academic) intellectuals of a sort that Rice turns out to support without holding them gratuitously hostage to the professional academic rules.

I met Jeff at a distance when a mutual friend, Bill Stranger, recommended him as an intro writer for the first volume of my book, Dark Pool of Light: Reality and Consciousness. Jeff came through big-time. I didn’t know his work at all, just knew that he was chairman of the Department of Religion at Rice and had written a history of Esalen Institute in Big Sur: The Religion of No Religion.

Then earlier this year while I was fine-tuning a revised edition of The Night Sky, Frederick Ware, an American architect working in France and a long-time reader of my books going back to the seventies and Spaces Wild and Tame, told me that I just had to check out this guy Timothy Morton on topic of hyperobjects on YouTube. Though discovered as I was refining a final draft, Tim’s work quickly became integrated into a few key sections of my book; for instance, the chapter on “Quasars, Pulsars, and Black Holes” turned into “Quasars, Pulsars, Black Holes, and Hyperobjects.”

I sent an email to Jeff soon afterward and asked if he knew Timothy Morton, and he wrote back, “Like Tim’s just about my best friend here.”

Tim is relatively new at Rice (two years in Houston after UCDavis; before that, Oxford, Princeton, and Boulder). He was practicing not in the Religion or Philosophy but the English Department, teaching the Romantics and Victorians and How to Read a Poem among other things. Jeff by contrast had been at Rice twelve years, chairman of his department for eight (a stint just concluded).