Substack General Archive

https://operajupiter.substack.com/archive?sort=new

Driving the Labyrinth Archive with Posts in Reverse Chronological Order. The most recent, the Montreal-Maine post, was challenging to write because of the time difference between now when I am editing and posting it and 2014 when I originally wrote it. I am also limiting my proof-reading because this is meant as ephemeral writing, a prosody-like calligraphy, maybe not “post what you get on the first try” but one edit and one quick proof only. I can’t explain why I missed some of the most interesting shots and picked some of the least interesting things to shoot except that maybe the numbers on the photographs suggest that many are missing (like the interaction between the dogs and the squirrel). I think I deleted too much stuff randomly when I got warnings about lack of remaining computer space over the years.

Montreal

Montreal was our last locale on the labyrinth from Berkeley, California, to Portland, Maine. Since we were under no immediate pressure to complete the trip and had the use of a friend’s apartment for a week (after sharing it the first night), we decided to stay in Montreal for five days. When we arrived there on Sunday evening, our agenda other than wandering around the city was to visit various friends: Mary Stark and her husband Jia-lin, Andrew Lugg, Jesse Ning and his son Angus, and Wayne Turiansky.

At the time, Mary was my archivist and literary executor, so we communicated by email on an ongoing basis. I “met” her initially in the mid-eighties after she read Planet Medicine and The Night Sky and sent me an old-fashioned letter. After a lapse of a couple of decades we reconnected in the era of the Internet and, when I heard about authors (Maxine Hong Kingston, I believe, was main one) losing whole manuscripts and their back-ups in the Oakland firestorm, and given the threat of a long-overdue earthquake on the Hayward fault rendering our house irreclaimable, I took to emailing her updated files of my work as I produced them and she archived them.

I met her and Jia-lin in person for the first time in 2006 in Montpelier, Vermont, roughly halfway between our location at that time. They drove down from Quebec and I came up from Connecticut while Lindy was attending her fortieth reunion at Smith. Then in 2010 before flying back to SFO, Lindy and I took a long route from Maine to Logan Airport in Boston, via Quebec City, Montreal, and Vermont, and stayed in a cottage that Mary’s family owned near their house in suburban Beaconsfield. That gave us a chance to visit her and Jia-lin for a few days while we explored Montreal.

That was not our first (or even second) visit to the city. We drove to Montreal numerous times between 1972 and 1977 when it was the closest metropolis to our home in Plainfield, Vermont; in fact, it was close enough for day trips. We even attended a Montreal Expos/New York Mets game at Parc Jarry sometime around 1973.

Andrew Lugg was a more recent migrant to Montreal. He and Lynne Cohen were among our closest friends in Ann Arbor during the late sixties. He is an academic philosopher, originally from England; she a museum-quality photographer. In fact, she was working in Quebec City on commission when we passed through there in 2010, so we got to reconnect with her and Andrew for the first time in decades, a visit I wrote about in my book The Bardo of Waking Life. They lived in Ottawa for most of their professional lives, both of them teaching at the University there; they moved to Montreal after Andrew’s retirement.

Lynne passed in May before we arrived after three-plus years of lung cancer, an ailment diagnosed not long after we saw them in Quebec. I was not sure that Andrew would even feel like visiting, having old memories stirred up by another couple with whom he and Lynne shared a 1960s past but not much since, especially so soon after his ordeal, but he encouraged us to visit after I sent a feeler from Toronto.

Jesse Ning was my most recent Montreal friend. I met Jesse the previous summer, along with his wife Lucy and son Angus, at the trailhead for Parkman Mountain in Acadia National Park. That day I had driven there with a plan only to hike the Parkman-Bald-Mountain loop, not much more than an hour’s climb and return. They planned a three-mountain loop that included Sargent, the second highest peak on the island at almost 1400 feet, an overall hike of more like five hours. At the trailhead, Jesse approached me, a stranger, for advice on their hiking itinerary, and, after we fell into easy conversation, I elected to walk the full loop of trails with them.

I never got clear during that hike, or even later that day when they came to our house to meet Lindy and for tea and dessert, exactly where they were born and raised or presently lived. Since they were Chinese and lived in Beijing, I assumed that they were Chinese nationals who had bought a second home in Montreal. While Angus was between junior and senior years at Brown then, majoring in philosophy and applied mathematics, I assumed that he was a Chinese rather than a Canadian student in the US. Lucy was an M.D. in Beijing, but she got her degree at UCSF in the Bay Area where the family lived for a while—Angus was born there. In truth, I learned in Montreal they were native Quebecois, Chinese Canadians who had evolved planetary citizens.

In the course of our 2013 hike, I discovered that Jesse was a wide-ranging entrepreneur specializing mainly in editorial ventures. Having been the publisher of the Chinese version of Elle as well as other big-market mainstream magazines, he was on the verge of launching broader ventures including books on health and other topics with a partner in Baltimore. During the hike he proclaimed an interest in our staying in touch with an eye toward possible business ventures together and, while at our house, he bought a number of my own books, for family members as well as himself. We exchanged some hello-goodbye emails during the year, but I did not expect to meet up him in person again anytime soon. Yet while Lindy and I were in Texas, Jesse (a reader of this travel journal) emailed to see if I was in Maine yet and, if so, whether we might get together to discuss Chinese rights for some of North Atlantic’s alternative-medicine titles. I wrote that we were in Austin but would soon be in Montreal. He was already there, working at his family’s hotel, a venture he hadn’t mentioned on our hike.

Wayne Turiansky was a poet living in Vermont during our time there teaching at Goddard (1972-1977). Lindy and I not only included him in the 400-page Vermont issue of Io but, after we started North Atlantic Books in 1974, initially publishing writers only on grants or by donations, his book Sand Cast became the fifth or sixth title in the series. Wayne’s short “long” poem had to do with an unrequited romance and a road trip across the country, the picture of the coed at stake gracing the cover.

Back in the seventies I learned that Wayne’s grandmother Lillian Brown owned Brown’s, the hotel in the Catskills geographically closest to my family’s resort and named similarly after the founding family. Though quite a bit smaller than Grossinger, Brown’s was part of its recreational, entrepreneurial, and ethnic gestalt—the boorishly epitomized Borscht Belt—and flourished and then faded in roughly the same three-quarter-century period under the same regional, economic, and cultural forces.

I lost touch with Wayne soon after we left Vermont, but I had recently found and friended him on Facebook. I had been searching for Io contributors in present time in order to ask their permission for their work to appear in a fiftieth-anniversary anthology scheduled for 2015. I never quite determined where Wayne lived these days, or where he had lived in recent years, Montreal or Vermont. It turned out to be both places: he had been commuting for a long time.

After Lindy and I exited 15 south from the Laurentians, we proceeded such a long way down St. Denis that we were sure that we had overshot Pine Avenue, the next landmark on our map. In fact, we should have been looking for the Avenue Des Pins, and luckily we caught the potential “lost in translation” sign in advance on the car GPS and made the right turn.

Thereafter St. Denis became our neighborhood and compass. We returned to it many times, to walk, to eat, to window-shop, to sightsee, and to get going in both the right and wrong directions, the latter more times than you would think possible in a mere five days.

Montreal is Francophone, and its underlying bilingual status has a subtle and profound effect on an Anglophone’s interactions with local habitants—bilingualism is deep-seated, a habitual state of mind. In all of Quebec, in fact, language carries cultural and political ballast, to the point being incendiary, as the province intends to keep its French heritage within a larger, mostly English-speaking nation on the border of an English-speaking, imperialistically Anglophile empire (as well as under the pressure of general international Anglicization). English has become the world’s de facto Esperanto, its corporate lingua franca.

Montreal has a notorious cadre of language police who go around town seeking illegal Yanqui drift and issuing criminal citations for English signs with words and even the verbal use of English by civic employees, shopkeepers, and other regular folks. At one extreme, linguistic vigilance is necessary to stem the flood of Anglicization; at the other it is fascistic to the point of a theater of the absurd, with people being fined and even threatened with jail time for trying to make themselves comprehensible to other human beings. [A Quebec-based friend notes, “It is not that draconian, only treated as such by the Anglo media. I have never heard of jail time.”]

For the record, any particular language is an arbitrary band within a broader spectrum of phonemes anyway, all of them (on Earth) originating from some Ur Indo-European/Sino-Tibetan babble that, along with all ancient dialects as well as animal call systems on the planet, originated in Noam Chomsky’s deep syntax—the neurological pathways and logic strings of the chordate, then mammalian, then primate brain. All terrestrial languages are finally variants of the same language, biologically and psycholinguistically, so why valorize or criminalize a particular melody? It’s all the same basic song. On the other hand, you would hardly want to relinquish the distinctive sounds of Stéphane Mallarmé and Edith Piaf under a deluge of corporate English. After all, French has a distinctive aesthetic beauty, soul depth, and meaning set. A semantic conundrum for sure.

We never encountered any reactionary blowback against English in Montreal (as we had on occasion in Quebec City four years earlier), but we did have to engage in a constant give-and-take while navigating a gamut of varying responses, most of them happily and graciously on both sides. They coalesced along the tension lines of our only speaking English in a French-preservation zone. People’s French instinctively held its ground as both the conversation-initiating and default tongue, even for English speakers because they had been daily sensitized to the ongoing cultural and political issue. At widely diverse skill thresholds of English, the speech of individuals flowed back and forth across an elusive line that separated us gringos from them, a line that was not tipped off by a given person’s dress, style, appearance, or mien. We got to experience a small sample of limitless variations on the theme of “English meets French” as well as “English meets Franco-English in a Français-speaking Zone.” Montreal residents had performed this delicate semantic dance for so long that they had developed diplomacies and linguistic traits that were, for the most part, subliminal yet honed to black-belt level. So, this was even true for English speakers in Montreal: two Anglophones initially had to acknowledge and discount that they were engaging verbally in a French-speaking zone before resorting to English.

My initial Franco-Anglais experience came very soon after arrival when, after helping to unload our items into the apartment, I tried to figure out where to park the car long-term. Streets signs were of course all in French. I understood from our hosts’ explanation that we faced multiple regulations: spots okay for people only with a numbered neighborhood sticker, spots okay except on street-sweeping days (Mercredi and Vendredi in our near vicinity), mirage spots not okay under any circumstances (and for no discernable reason), spots okay if you walk to the credit-card machine, register your parking-space number, and pay. It was unclear to me how they checked without printed coupons on the dashboard, but a friend later told me, “There is a central computer that has its eye on you.” Add to this the complication that cones were later placed around our quite legally parked car, turning much of the street into a sudden towaway zone for electrical work.

So , when our written instructions from Arnie (see the previous post) seemed to contradict my rough translation of the French signs, I stopped someone educated-looking, who turned out to speak very little English. While puzzling over the instructions with me, he finally concluded that I couldn’t park where I thought I could because I needed a numbered neighborhood sticker for the location. As I stood there pondering my remaining options, he marched all the way back from farther down the block not only to point to a small sector of spaces that did not require the sticker but to indicate the one that was available and to hold it while I hurried. Any tension I might have felt from “forcing” him to speak English was dispelled by this generous act.

The following morning, I went out for a walk in my the five-fingered shoes I wore periodically then. Steve Curtin, an osteopath in Maine, recommended them on the premise that they are therapeutic for spreading out toes and ameliorating, among other things, neuropathy. They make one feels as though he suddenly has ocelot paws and is about to take off after a rabbit. In my first quarter-block in these shoes I was stopped by a dapper man who began speaking French to me. Since Lindy and I had already been approached by two or three French-speaking panhandlers, my initial response was to disengage. He grokked at once that I didn’t understand him and switched to broken English, asking whether I liked the shoes (while pointing) because he was thinking of buying a pair himself and had read some negative publicity. I gave a thumbs-up followed by an explanation. He nodded and then, as he turned, spoke in disparity to his previous stumbling jargon, “Hey, have a great day, man,” as if having memorized a set phrase at a higher tier of English.

A less beneficent encounter took place a few days later when, on a visit to Old Town we ignored the shouts of a homeless person in the Champ-de-Mars tunnel leading from Vieux Montreal back to the Metro. When we did not respond to his blandishments (and had no idea what he was saying either), he attached himself to us, following and then trying to block our passage while continuing to shout in our faces. It was lucky that we were in Canada because, in the States, he might have been armed. Lindy finally said, “Would you please get out of our way. We are just trying to get on the subway.”

That unpromising ploy surprisingly worked; he wheeled around while continuing to walk backwards and address us: “English you want, aye? I speak Anglais. I’m from Nova Scotia. I tell ya, everyone here is nuts.” As we kept walking briskly, he fell back to harangue another pedestrian.

My favorite instance of language dissonance occurred at the custodial booth of the Laurier subway station, but I will save that story for later.

We began our stay in Montreal the first night by heading to St. Denis for dinner. There were so many restaurants in our stretch of the avenue that it was almost a surprise when an establishment was not for dining. We had a working list of favorites from our hosts but chose one off theit grid: Shambala, Restaurant Tibétain, right next to a Coréen eatery: up the stairs and around. The waitress switched from the French she was using for the couple before us to English when we had said little more than “hi” and probably not even that. I think that we must have been breathing English. The menu was in both French (large) and English (tiny and underneath). Diners at tables around us spoke French, except for a loud Anglophone couple in a vocal duet surrounded by diffuse jazz.

The next morning, Monday, was fully choreographed by planned visits with friends. Mary had the week off her job at a community retirement center but replaced some of those hours with the responsibility of shepherding Russell, her nine-year-old nephew from England, back and forth to French day-camp—so she was flexible but not a hundred percent so. Her partner Jia-lin was up to join us at just about anything. Andrew was trying to juggle us with another friend who had showed up in town unexpectedly but was insistent on finding a time for us and willing to prioritize it. Jesse wanted to be sure that we got together before he left for Beijing, so he immediately pinned down dinner that night.

I had a vague goal of putting Jia-lin and Jesse into conversation as Chinese nationals, especially since Jia-lin had expressed, through Mary, that it made no sense to him that we had met a Chinese family who lived in Montreal in the way that I described. In fact, it would be discovered a couple of nights later that Jesse grew up in the same Montreal neighborhood as Mary and attended her high school seven years after her graduation. You don’t have to follow all this. Just note that synchronicities blend with six degrees or less of separation.

I finally settled on compatible dates and times with all parties. Mary and Jia-lin would meet us at our apartment as soon as they dropped off Russell at camp. We would hang out together until they had to leave to pick him up—they needed an hour’s drive time back to suburban Beaconsfield. In that span we would try to eat lunch, go to the art museum, and visit Jesse at his hotel.

Initially I didn’t understand why Jesse was staying at a hotel if he had an apartment in Montreal. In fact, these were one and the same: his family owned Hotel Ambrose near the art museum. Having bought it three and a half years ago, they were still working on fixing it up. While in town, Jesse and Angus were part of the collective clan effort. Meanwhile Lucy had stayed back in Beijing with their twelve-year-old daughter. That I was mistakenly still thinking of them as Beijing-raised was immediately cleared up later that day in the lobby after lunch.

Rain threatened, so we took umbrellas. Jia-lin declared right off that Mary was boss and, in keeping with that hierarchy, she led the way and drove, but he directed peremptorily as if he were a trained guide and we were all tourists. After having escaped the brunt of the Cultural Revolution as a young intellectual in the seventies by going into hiding, he barely made it to Canada on a literary scholarship, an unusual feat for Chinese at Concordia University. Then he married Mary and got to stay. For years I developed an apocryphal account whereby Leonard Cohen introduced them as, in Mary’s initial telling of their history as a couple, the Montreal-based songwriter and poet came up as having something to do establishing conditions for helping political refugees like Jia-lin remain in Canada.

Indefatigably cheerful, Jia-lin seemed to be celebrating every new Canadian day as a sojourn in paradise for its not being a day in Mao’s China. A sense of innocent wonder and joy as well as an innate beginner’s mind had not worn off even after decades in the New World. He was buoyant, exclamatory at each next thing, and bounded ahead on multiple occasions to scout for restaurants and, later, for the entrance to our parking garage which we seemed to have lost while wandering in search of it under umbrellas. But he also insisted on barking out instructions in keeping with his role as Montreal’s unacknowledged avatar. He was the stranger in a strange land who had taken it over.

After we made do at a drab (cuisine-wise) but otherwise spiffy downtown Chinese eatery, Jia-lin ordering unknown dishes in his native tongue, we headed out on foot for Hotel Ambrose, having conceded that there was no remaining margin for art-museum tarriance, our initial goal, before nephew-pickup time. Ambrose was, as represented, a residential hotel. In fact, we could not imagine that there would be a commercial establishment on its apartment-filled street and, from the outside, it was a barely converted apartment building, only a “hotel” sign distinguishing it from the other stone façades. The woman at the front desk directed us to the lobby while Jesse’s whereabouts were sought. After about ten minutes he joined us (looking quite a bit younger than I remembered him from the hike—context is everything). We sat there talking, settling matters of residence and lineage (as well as Jesse’s new publishing venture). Meanwhile the hotelier enumerated in detail what a hassle fixing up an old boarding establishment was. “You should know,” he said to me. “Your family was in the business. I don’t know how people make money at it. The banks know, though; they won’t give you a loan if you’re using a property for a hotel.”

Interspersed with our banter, Jia-lin engaged in a side Chinese conversation with Jesse, while brushing off Mary’s instinctively prying inquiries into what he was saying (knowing well from the exchange’s tenor and his expressions that he was up to something). By the time we were leaving, we learned what had happened: Jesse and Angus (who was off painting a room, so not in present company) had been invited (and Jesse had accepted for them) to a gala Chinese meal that Jia-lin proposed to cook on Thursday night: all his own original recipes, he insisted repeatedly (because Jesse had told him he would come only if he cooked anything but Chinese food).

Jia-lin is, as noted, continually feting his freedom and celebrating everyone’s affability, at least by comparison with the Red Guards, hence the spontaneous invitation in the Ambrose. Mary then explained to Jesse that when Jia-lin cooked a meal, he invited the proprietors from all the stores at which he bought ingredients—and some even came. When the two met me several years earlier in Vermont, Jia-lin had invited the American border officials to dinner in Montreal! In some regards his gruff, passion-filled enthusiasms suggested to me the Chinese version of the Okinawan karate master working as a custodian in the San Fernando Valley as portrayed by Pat Morita in Karate Kid.

After Jia-lin found our lost garage and Mary dropped us off at our apartment, we had only a couple of hours to rest before Jesse showed up anew, this time with Angus but also his unexpected, cheerful sister Chin. “She read your book,” he explained without further elucidation.

For me the back-to-back events marked the beginning of crashing physically and mentally. We had been on the road for over a month, having driven more than 4800 miles. From that afternoon through the next day or two, I struggled for enough energy and emotional stability to keep going. I fell into a familiar anxious, migrainous state that colored everything, plus I had a very swollen left foot from having tripped over a suitcase in Ann Arbor and a cramping back from too much driving. Everything that follows that day and the next took place in a sort of a sleep-walking haze.

As Jesse and crew arrived in the evening, we were reintroduced to Angus as a recent graduate of Brown headed to his first job, an illustrious gig with Dreamworks in their animation and 3-D modeling department in Shanghai. While awaiting for his visa, he was joining in the family project at the Ambrose. “I guess you did ‘brush on, brush off’ all day,” I said (Karate Kid still in mind).

“No, just brush on.”

We dined at an Ethiopian restaurant on St. Denis; Jesse and Lindy noted simultaneously that it bore the same name as a favorite one from the eighties in Berkeley on Telegraph, long gone, but I sensed an indigenous trope more than an emigration from the Bay Area to Quebec. It was The Blue Nile or “Nil Bleu: fine cuisine éthiopienne.” The evening went by in a thump of community-style food platter set-downs, bread for picking out pieces of meat, vegetables, and mashed roots (in lieu of utensils), Jesse regaling us all the time. Angus was remarkably restrained, showing only hints of irritation at his father’s loquaciousness. Though I had a headache and the kitchen mixed vegan and meat dishes on the platters after not only promising not to, it was otherwise a delightfully high-spirited evening.

The next morning the view across the street where statues of animals and cartoon characters were posed dramatically on the fire escape was even more amusing, for a woman was yelling in French while shooing at her windowsill. A squirrel went scurrying out of her apartment onto the metal grid, down one flight, then onto a Philippe Petit narrow ledge of raised stone, around the corner, and down the alley.

All we had planned for the day was lunch with Andrew at a café so close that we could walk there in under two minutes.

I think that we originally met him and Lynne in Ann Arbor out of our mutual interest in avant-garde film. He was part of a group in charge of the film society there as well as being a graduate student in the philosophy department. After we moved to Maine and then Vermont, they moved to Ontario. One of the Lynne’s first publications in the mid-seventies at the onset of her distinguished career was a series of photographs of kitsch, Naugahyde, TV-set-dominated American interiors in Io/19. Her portfolio, established over decades, was based, in part, on her turning tacky or not-so-tacky industrial, urban, and otherwise mechanized landscapes into aesthetic compositions.

After Vermont, the four of us dropped out of touch with each other for most of thirty years until a mutual friend in Berkeley, Rick Ayers, a North Atlantic author IBerkeley High School Slang Directory), gave me their contact information in Ottawa. A local public-school teacher and brother of Fox News’s whipping boy Bill Ayers, Rick had been in Ann Arbor in graduate school at the same time as the four of us.

I was going to leave our lunch with Andrew out of my blog, as it is difficult to achieve the respect and dignity necessary for the practice of grief. Yet I also want to alert my friends to Lynne’s amazing work. The compromise I achieved was totally with the help of Andrew who is now curating her large collection of photographs, placing them in exhibits, books, museums, etc. In fact, I will get to that first by inserting relevant section of his later email into my text (fewer now than then, as many links have expired in the last eleven years):

“The video in which Lynne plays a supporting role follows (below). There is also a short item in which Lynne discuss her show here last year. It starts in French but shifts to English a little way in. I especially liked the segment of the “Light under the door” picture. Click here:

. Also I’ll throw in a nice tribute to Lynne in the National Gallery of Canada magazine: http://www.ngcmagazine.ca/artists/remembering-lynne-cohen. . . .In the Calgary Herald, Cohen’s voice is halting and choppy from the radiation, the veins in her arms badly damaged by chemotherapy. Her husband, Andrew Lugg, is seated nearby.”

At lunch, Andrew and we talked about the intersecting issues that affect us most deeply as we age: identity, mortality, marriage, death. In his direct presence Andrew was trailblazing, modeling what we all face: our own final passages, the prior passing of a life partner—how to grieve and yet live, live with the unbearable, the new normal. His gentleness and good humor, some of it perhaps ingrained English fortitude, were illuminating and encouraging. You finally survive only moment-to-moment while trying to ride the roller-coast of unpredictable emotional shifts. A few years later, a therapist I saw in San Francisco for almost two decades, Gene Alexander, wrote me one of the best descriptions of this process I have ever seen:

“i think it works like this: you think about the loss and instead of trying to control things you accept the possibility and the grief that comes with it. it feels like you, yourself, will die if you allow the feeling of sadness to have its way. but slowly, very slowly, it visits you because.....well, I suppose because it is there....and you survive the emotion. Perhaps in this survival of sadness and loss one begins to realize the beginning of a sense of self. not a self held together with paranoid vigilance, not a self made safe through control, anxious ritual, or worry, but a self that has come back time and time again from loss. . . . Remember that story about faith i told you once? that we have faith because we ‘kill’ our parents and then discover that they are still there, psychologically intact, and we realize that there is an ‘other’ who is truly separate from us? Well, maybe the self needs to die of grief and then return for us to create the plug that was never put in place.

“In facing the death of a close friend and the illness of others, I have seen that I will, that I have to, come through this and that I have to not just grieve, but grieve in the service of coming back to living. isn’t that what we all want from each other? to love and to grieve and to live again?”

It’s not af if we have any other choice, except perhaps to die, or to live in degrees of solipsistic sorrow, a tantrum against the universe.

Just having this time with Andrew increased both recognition and courage. I noticed (twice) how he started a sentence as “we” and then almost indiscernibly switched to “I”. When you have been a couple for so long, it is always “we” internally; But you can’t be a “we” if one party is in the world of the living and the other in the land of the dead. On the other hand, “we” is intrinsically a social convention because you never cease being an “I” who is in relationship with another “I.” One of the features of life in this plane of the cosmos is that entities are never inter-subjective. You are born and die as an “I.” The couple’s “we” operates in a lay legal sense, also as a plural pronoun of convenience.

The youngish maître d’ at the restaurant knew Andrew by sight because he and Lynne came there regularly. When Andrew explained in French that Lynne was no longer here, the man was visibly shaken. The two talked for a while. Later, as we were leaving the restaurant, a waitress stopped Andrew and they engaged intensely while Lindy and I continued onto the street. He told us later that she was crying. He himself continued to absorb this incident as we walked to St. Louis Square to sit in the park by the fountain.

The Square had once been a drug hangout but now was in a stage of reclamation, so it was still a mixed habitat, homeless people and drunks among couples and well-dressed professionals sitting on wooded benches and the stone masonry encircling the fountain, many having their lunches.

What does Andrew do these days? He writes about a couple of philosophers; he reads; he sees friends; he collates Lynne’s work; he lives out his decision to be in Montreal and laughs inwardly when people wonder if he’ll go back to England (where he hasn’t lived since the mid-sixties—he isn’t English anymore). He talks of his wife easily in both the present and the past, her presence when lecturing, her commission photographing in Venice not long ago, their travels in the Soviet Union (quite long ago), her wish not to have him attend her lectures, his standing outside the door anyway, her late good humor along the lines of “we all have to die.”

Six squirrels gathered at one patch of lawn to share the droppings of two men eating lunch, the most I have ever seen together. They treated one another quite well compared to gulls, plus their collective bushiness was compelling, cute from a human view.

A rough-looking, burly tattooed young man with a diffident “fuck-you” attitude took off his shoes and socks, rolled up his pants cuffs, and got in the fountain bearing a tiny furless dog. He then set the unhappy pup paddling for dear life as he worked his way across the circle alongside it, something a hair less than a full diameter (which would have been blocked by the spout). Periodically he lifted the dog out of the water, but its legs never stopped paddling, even in his hands, a painful sight to observe, as he then set it back in. When he reached the other side, he removed the animal from the bath, retrieved his footwear, gave everyone a sweeping glare of appreciation, and continued toward St. Denis. [Two nights later Lindy and I watched a guy arrive on a bicycle, take off his clothes except for underpants, bathe in the fountain with soap, and slowly and meticulously towel off on a bench. Remove his bike and he looked like the other homeless men who used the park as a bedroom and toilet.]

A couple on a bench near the fountain was having an escalating argument. First “he” sat on the bench while “she” remonstrated wildly, arms punctuating insistences; then they both sat while he emphatically issued rebuttals, punching one hand with the other.

Our discussion with Andrew awakened some of the slumbering anxieties and vulnerabilities that informed our trip, life passages that were never far from my mind anyway. The title of a book by Stanley Keleman, a bioenergetic therapist for whom I worked as a freelance editor in our early days in Berkeley (1978), resonates with this implicit epigraph: Sexuality, Self, and Survival. It’s always the given state, for every animal, no matter its status or age.

In a very different vein, my long-time psychic friend, astrologer Ellias Lonsdale, finds countless ways to point out, taking the long view, that the primary difference between life on Earth, at least in this plane, and life elsewhere in the universe and on other planes is that here when the dead leave, they are gone forever; we have no idea how to find or address them. Yet they are somewhere, for they are real. He claims that this disconnect is a local aberration but a crucial one in the karmic evolution of human consciousness.

Leonard Orr, another North Atlantic author and founder of Rebirthing, touches on a different aspect of the same theme in the title of his book with us: Breaking the Death Habit. To Leonard, breaking the widespread human habit of dying is half an authentic yogic and psychological exercise, half a parable and metaphor—he also means it as stated: death is a deeply ingrained habit indeed, for just about everyone adheres to it: corporate bankers, terrorists, priests, healers, pornographers, crooks.

By using Andrew as a sounding board for our reasons for leaving Berkeley, Lindy and I were able to articulate one of them more clearly than before we bolted: very simple—we didn’t want to die there. Both together and separately we didn’t want that. For a whole number of different reasons such a fate was unthinkable, hence it was absolutely essential to get out while the going was good—while we were physically able. We were in the process of competing an amazing getaway that, in its full scope, had consumed the better part of a decade: first buying a house on Mount Desert; then building a second life and community presence there; then (the activating breakthrough) preempting our primary residence by buying a home in Portland (last December); which allowed us (next) to sell our Berkeley house (in June); then cutting down on our belongings; packing up, greeting the movers with their van, getting in the car, driving out of town; now approaching the last baffle of the labyrinth in Montreal.

We took leave at the fountain, hugged, and headed our separate ways.

Wednesday morning, Lindy and I set out on foot along St. Denis with an ambitious goal of hiking maybe a couple of miles to the museum district where we had been earlier in the week with Mary and Jia-lin. This was probably unrealistic anyway, but it became absolutely impossible when we walked for almost an hour in the wrong direction. You might ask how that was possible since Lindy map-quested it and we had a street map of Montreal as well—but we managed. For one, she forgot to bring the list of steps she had carefully copied from online. For two, the map was in tiny print, hard to read, and left out too many intervening streets. Mainly, however, it was because Lindy marked our starting point on the map at a completely wrong spot based on a name that resembled the name of our street; thus, our landmarks on St. Denis were wrong from the get-go and we invented a false reality to cover where we actually were.

But it’s not as though the miscue was much of a problem. In a strange city it is enjoyable to walk anywhere and peer around. Sights, textures, and regional differences hold one’s attention and support one’s mind, so the landscape is entertaining, relaxing, and internalizable—factors rarely in play on one’s home field. French language streams and bright colors of Montreal added to an intrinsic pleasure. There were so many brilliant rainbow-painted buildings and primary-color kitsch and manga posters and graffiti that I found myself taking continual snapshots on my iPhone.

I was recalling an American avant-garde filmmaker from the early sixties—Taylor Mead, I think—who appeared in the Film Makers’ Cooperative Catalogue with a documentary of Europe under something like the following precis: “So much to shoot and not enough film or cash, so I set the camera on single-frame.”

That’s what his movie was. I never ordered it for our Amherst series back or saw it myself, but I assume that it was hundreds of photographs of Europe in a fast-moving time-lapse like an animated film or one of those autonomous hypnagogic downloads the brain sometimes unexpectedly makes of its inventory of images—thousands of them, unbidden, unconnected, and at different scales. I was logging a more mundane version of such a film in Montreal—it’s not Kodak anymore, you can trash it anytime and reuse the dollop of drive space. Using iPhoto, I became a daily spectator of my own Taylor Mead show, anywhere from a dozen to sixty images per loop. (Sadly I didn’t post or save most of them.)

Another bewitching activity was looking at people. One does this anyway. I instinctively read faces and shapes like tarot cards, feel for the energy of each passing hominid, notice the pretty girls and get whatever pheromones and biological charisma they are emitting (probably from ancient chordate hard wiring), diagnose the odd-looking, odd-acting, and generally eccentric folks, including tattoos, primps, degrees of agitation and acting out, and assorted nuances. I know that Lindy more closely checks clothes, hairdos, and general stylishnesses while constantly comparing herself and considering new ways to dress, new barber cuts to try, attitudes, pouts, and smiles to model. Meanwhile, I view shop windows like abstract paintings unless there’s something I am especially looking for, whereas she window-shops with the potential of going into any establishment and browsing, especially where there are dresses hanging or on manikins, or shoes, the more shoes in the window the more enticing the venue. She also looks at herself in the glass whereas I try not to see myself.

On this walk I drifted into an exercise that continued to some degree or other throughout our time in Montreal. It went something like this:

I know none of these people nor will I see anyone I know, but how do I actually tell myself (1) that a person is not someone I know and (2) that he or she falls within the range of acceptable human features and physiognomies, the basic gene pool, i.e., is human and of this planet and species? In other words how do they not get a second glance even though they are utterly novel? Why are strangers not more startling for not being known. This is a remarkable thing because the “emic” variations are so exquisitely slight. Everyone in fact looks like everyone else, and the distinctions are not easy to measure or articulate: exact size, shape, and tilt of a nose, coloration of hair, discrete expression, posture, carrying of haberdashery, the rhythm and syncopation of gait. It is remarkable that everyone could look so normal as to be beyond a second glance, yet so obviously not be someone I know that I don’t have to interrogate at all to reach that instantaneous conclusion. Variations that are exquisitely slight are still absolute and irrevocable.

Another theme that influences this equation is age. When you get to a certain time in life, you understand that, even if you were to see a familiar person, enough years have passed since you last saw him (or her) that you would not be looking at the same person but someone else much younger: a son or daughter or, more like, someone who got a few similar genes or epigenetic synergy from the species pool. Most people you knew decades ago would be unrecognizable from having aged. If they happened to pass by you, they would be anonymonus among the masses, long ago having turned into someone else.

This rule was “proven” by its exception about seven or eight years prior at the Common Ground Fair in Liberty, Maine. I was wandering with expectations of seeing only people from the time since our return to Maine but certainly no one from when I taught at the University of Maine at Portland-Gorham (thirty-plus years ago). Yet during those two years in the early seventies I had contact with well over a hundred students; they were Mainers then, and they were somewhere now, percentagewise more of them in Maine than not. Thus it would not be a shock if a handful of them were among the thousands packed into the fairground—I would have no way of knowing. Yet one ex-student did recognize me. Mary Doggett, an old favorite from the Portland campus; she had attended a number of my classes with her earnest, appreciative attention. I would not have recognized her; she was a young, slight girl then. Now she was a stout, gray-haired grandmother who had been farming for her whole post-college life.

How about those lookalikes of movie stars whose photographs were taken fifty or a hundred years ago; they could pass for their alias in every respect: the reincarnation of not only Edgar Cayce but everyone else

Another theme: a few years prior, I read a book called The Last Human. Its premise is that many other human species became extinct or were exterminated by Homo sapiens during its Stone Age evolution. The authors then reconstructed images of what each of these lost hominids might look like if walking down the street today. I can attest that none of them would have passed without stopping traffic. They were legitimate aliens, true proxy ETs. I saw none in Montreal.

I had more of an ET experience in Trieste, Italy, in 2006 when Lindy and I walked through a vast street fair that went on block after block in all directions. A number of people in the dense crowds were unlike anyone I had ever seen or imagined; they defied norms and wildest expectations. Their features were larger or more spread-out, their shapes eerily broad or long, their coloring and curves unidentifiable by race. They had a deeply foreign, boondock ambiance. The stroll in Trieste also gave me a sense of how many human beings there are on this planet now, a mind-boggle reinstated by wanderings in Montreal. Back then I wrote: “We walk through the hoopla and energy silently, scanning and absorbing it. There is so much to see, so many unusual faces and bodies, such beautiful teenagers and young men and women, dark Italians, magnificent Ethiopians and other Africans giving the fair a pan-Mediterranean seaport feel, fantastically eroded elderly people, madonnas and boticellis, bambinos whose faces for centuries have been cast have in manger scenes—so much color and light.”

As I pondered not knowing anyone in Montreal and—no one even a reasonable candidate for someone I knew—I considered the possibility that, on top of what can be seen or interpreted on the street by the usual visual cues, an unconscious recognition factor may be at work, including vibrations of the person on other planes such as the etheric and astral. If so, then another’s being and aura are “looking” at you, while you are picking up their whole being unconsciously, with no way to pass that information on or process it consciously—they are two separate platforms with no pass keys. Yet subliminal information is being psychically transferred as you and they silently and briefly say hello, even without meeting each other’s gazes or attending them. Under unconscious signatures of psychic recognition and information-exchange, everyone is passing anonymously and automatically. These two events are happening at the same time without any conscious bleed. We are like automatons: the fact that we don’t recognize or know how to find the dead begins in the fact that we don’t recognize or know how to find the living, not whole beings anyway.

Then I considered that a few people who inexplicably looked somewhat more familiar might have been known to me karmically or in my aura or Akashic record; perhaps they were from my same group soul, perhaps from other lifetimes. I am not stating a belief system as such, just recounting some of my idle considerations as we walked and I played this game with part of my mind.

In any case, we confirmed that we were going in the wrong direction by finally asking someone. Quickly changing to English, the woman weighed our plight. The museums we were looking for would have been far even if we had gone in the right direction, but now, after an hour of regress, they were out of the question. She had an elegant solution, though. She pointed down Laurier, the side street on whose corner we conversed, and explained that a subway stop on the Orange Line, a Metro station, was only a few blocks away. If we took the train, we could be at the museums in no time—a click of her fingers.

Even her mention of an Orange Line indicated what we were up against: an entire underground cosmology. I knew the New York City subway quite well and had also learned to get around the far simpler butterfly of the BART (Bay Area Rapid Transit), but the Montreal Metro was a blank sheet. Not only didn’t I know the grid or its nuances and punctuations; I didn’t even know the map on which it was set. However, we had succeeded in the past at unrehearsed public transport without major mishap in London, Berlin, Prague, and Reykjavik, so it was worth a gambler’s shot.

After short walk down Laurier, the station appeared on the left, but its presence in itself was hardly a solution. Our new crisis was that we had no Canadian money and didn’t know if there was a custodian and, if there was, whether he could take a credit card. So Lindy stopped at a shop inside the opening to the station to see if the proprietor would exchange currency or sell a pass; meanwhile I went down the stairs to check for a booth with a live person. There was one, not near the entry like in New York, but at a much deeper level. I hurried back and retrieved Lindy from the onset of what would probably an impossible conversation. That began our most interesting French-English interaction—at the station custodian’s booth.

Luckily no one else seemed in need of assistance or wanted to purchase a fare. Everyone was happily entering and departing, smoothly flowing through the turnstiles. That left enough space for an entangled exchange inaugurated by a variety of factors: (1) it was noisy (both a footstep din and the racket of entering and departing trains); (2) the acoustics were poor (including the booth-woman’s scratchy microphone); (3) the window to the booth was extremely tiny, making wedging a map through it an origami function; (4) then Lindy has age-related sound-differentiation difficulty so wears hearing aids that tend to amplify background unevenly; she also experiences increased dyslexia at times of stress and reverses or otherwise mis-hears names and denotations; (5) she has more experience speaking French than I do, almost enough to get by, hence its own trap. The conversation started with her asking, “English? Anglais?”

A middle-aged, seemingly humorless woman responded, “Un peu.” [“A bit.”] This was, however, a tease because she proceeded to talk in perfectly fluent English. However, with all the acoustic factors at play, Lindy missed that and continued to try to communicate with her in both French and English. The woman was correcting her French while continuing to talk in English, enjoying herself mightily. I tried to intercede but got pushed out by both women who each seemed to relish the exchange for their own reasons, even as Lindy tried to scrunch the map more and more while pointing at it and wedging it through the opening.

In fact, the custodian was more irritated with me for interrupting their exchange as I blustered through my own set of know-it-all presumptions; for instance, that the system resembled New York or BART in ways it didn’t, that she wouldn’t take American dollars, that we wanted to buy a round-trip. I was wrong on all counts and, by the time I finally realized that I should back off and let the interaction play out, Lindy had purchased two twenty-four hour passes with an American twenty (that the custodian held up to the light for a surprisingly long time—by contrast, a single round trip would have been eleven dollars each for the two of us. The transaction was successfully concluded because the enjoyment of being lost in translation led to camaraderie and cooperation, and it wasn’t even really translation that was the problem, it was the noise level.

I then blustered further by acting on my presumption that you stuck the card in a slot; you didn’t. Lindy had been watching and had to physically restrain me from losing my card in a sterile groove. Instead, you placed it bottom down on a glass scanner and the gate opened. Then she told me that you didn’t need it for exiting like BART; people were just walking out the turnstiles.

After getting officially inside, we plunged down the wrong staircase and, if we had taken a train there, would have been continuing in the same direction along St. Denis. Luckily there were none present, so Lindy stopped a group of tattooed teenage boys and got us directed to the other side of the platform. Place-Des-Arts was the stop we wanted, in the Côte-Vertu not Montmorency direction. But first we needed to switch from the Orange to the Green Line at the exotically named Berri-Uqam station.

The Montreal subway has a butterfly shape similar to that of the BART but with more of a folding and curl. Berri-Uqam was a key switching node between wings, like MacArthur on BART. It wasn’t till we passed through it again in the evening that I realized the name wasn’t exotic at all. Uqam is actually UQAM: University of Quebec at Montreal.

The three things I don’t like about BART are: (1) It is priced by the distance that you go, so it is less an urban subway than a commuter line masquerading as a metro; you never get to play around with the grid and maximize your ticket. The fares are increasingly expensive. (2) You have to keep track of your ticket. If you don’t have it, you can’t exit. You are trapped. It is like losing your ticket for a parking garage: then you can end up paying quite a bit extra for the lost ticket. (3) You can’t get to very many places within any of the large BART cities, especially San Francisco. Each route is a single line through the grid, and it misses major urban territory. The curls and folds of the Montreal butterfly improve coverage. (4) This is not official because it is too much of a generalization, but I find BART unfriendly—Fruitvale Station unfriendly. Though I loved moving from rural Vermont to the edgy, sophisticated Bay Area in the late seventies, the counterculture has withered locally into artifacts, derivatives, and reactionary blowback. I wanted to get away an antipathetic self-absorption that seemed a regional Northern California trait—the condescending glance, the solipsistic stare into the distance or internal space, the professional, going-about-my-business/get-out-of-my-face attitude, the cool, laid-back boredom with humanity. In sum, people don’t connect as much in Northern California; the sense of community or pride in community isn’t as strong (though it is paradoxically stronger in Oakland than Berkeley or San Francisco or the suburbs, precisely the Fruitvale zone of that indicative and brilliant Ryan Coogler/Michael B. Jordan indy film). I don’t find that dissociated quality as generally prevalent in New York, Quebec, or New England. Those folks bond and help, go out of their way to help, so you feel a natural part of human community and camaraderie. They have other ways of being reticent and establishing distance

On the correct platform, Lindy struck up a conversation with a middle-aged woman standing next to us, a dialogue that continued on the train. Initially it was just to make sure we were on the right course and about to make the appropriate switch. This became a larger exchange about her job, editing books in “French as a second language” (FSL). That did, however, leave her halting English unexplained. She reassured Lindy that, unlike in France, “People in Quebec love it if you try to speak in French, even if you speak badly.”

We next asked directions of two elderly women at the first light on the street at Places-Des-Arts in order to get going in the right direction.

As we wound uphill, the combination of plazas and buildings was both daunting and entertaining—such spectacularly designed architecture, so much aesthetics and activity nested in each other, the mostly orange and blue and other camp colors of young children in groups adding to the overall esprit. The kids walked in lines or were seated in clusters among sculptures, fountains, and statues. Conceptual art pieces with mirrors invited pedestrian participation. Further along the plaza stood huge mural-like placards of native Canadians doing ceremonial dances, the background and meanings of each of the forms explained in French and English

Gradually the levels descended back into ordinary urban life, streams of people maneuvering through each other on a NYC-42nd-Street-like stretch (that was also generic touristy) below the museum’s plazas. That’s where we ended up, after checking out other options and selecting an Asian-fusion restaurant with an outdoor dining platform, but not before I left Lindy behind to read the Indian-dancer signs (as she walked) while I soldiered several few blocks more to see if there were better dining establishments; there weren’t. The scenery and rhythm became more like 57th Street; in fact, all of Montreal in that neighborhood radiated one New York tenor or another.

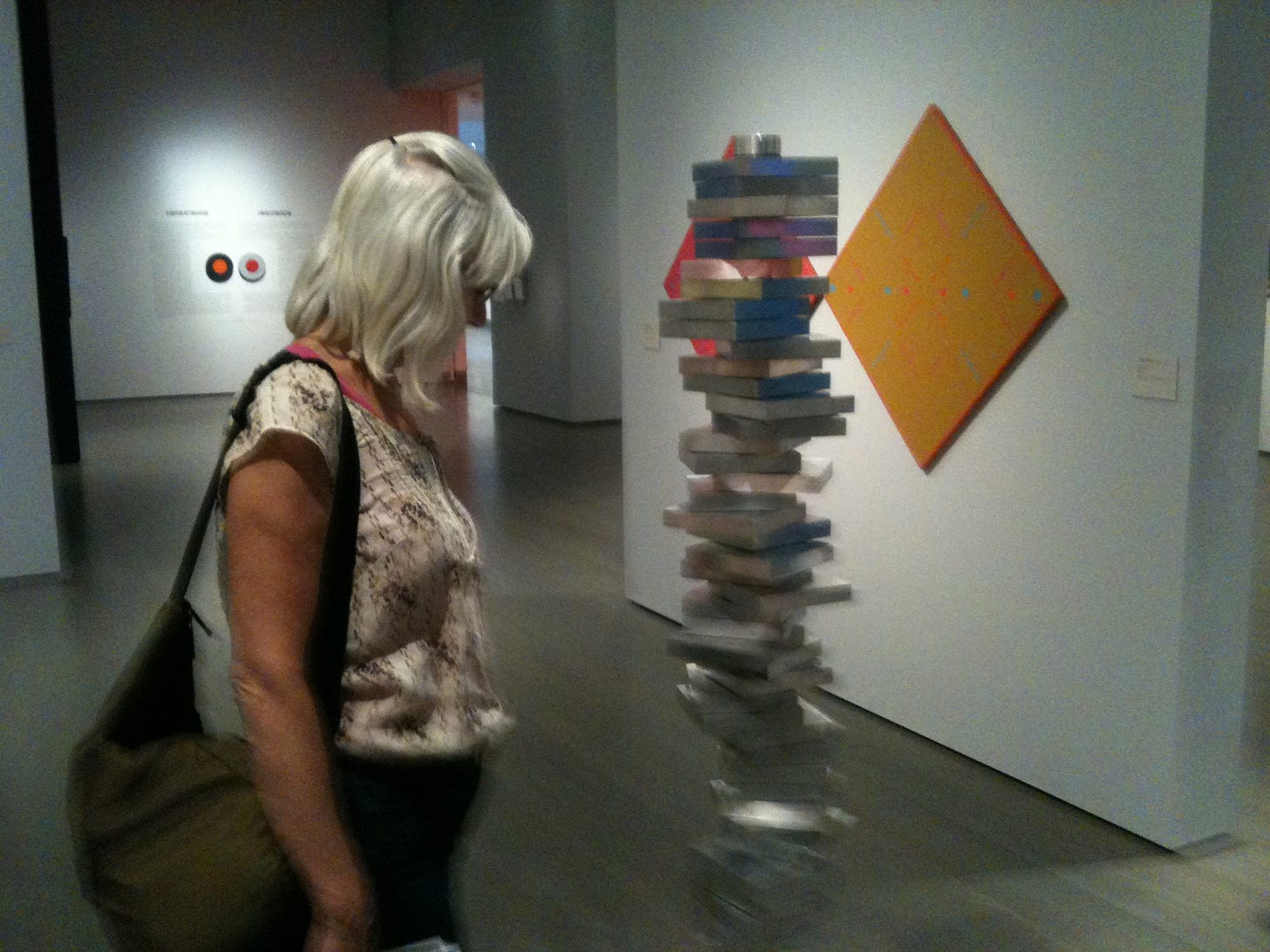

After lunch we selected the Museum of Contemporary Art (Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal) for our one indoor tour.

To pick up on a theme I initiated in my description of its Austin equivalent, I find that art museums these days are places for interrogating the act of the artistic view as much as for viewing art per se—and I mean that in terms as much of the physical and mental capacity to take in information as subtext and cultural deconstruction (though the latter is precisely what the artists and curators intend). It is flat-out difficult and depleting to look at artifacts for too long without becoming overwhelmed by the effort, both conscious and unconscious, to organize fresh information. After all, each piece projects its own history, biography, and cultural frame, yet one goes from piece to piece as if they belonged together or could be assimilated in each other’s contexts consecutively. The foiled attempt to do so leads to an oddly disjunctive splay and welter of meanings, most of them subliminal.

In the case of the Musée d’art contemporain, this condition was dealt with explicitly right away, for the first exhibition up the stairs (to which we were pointed after paying) was a horizontal series of serigraphs or serigraph-like prints or paintings, about nine of them in bright colors, by a Montreal artist named Michael Merrill. Titled by their hues—Cobalt Blue, Yellow Ochre, Cadmium Red, Gold Yellow, Spring Green, Breughel Red, Electric Blue, Grey, etc.—they were meant to depict as art the process of producing and then hanging art, e.g. themselves, in a museum. As such, they were the perfect entry item because their didacticism and banality of topic were alchemized into something compelling by the brilliance of their colors and sleek shadow-like imagery. The overall title of the series was “I Never Saw Documents.”

After that, we looked at a video installation by Canadian-Armenian film-maker Atom Egoyan, an oral history of a woman discussing her childhood initiation by her mother into the magic of a musical legacy by way of old, reel-to-reel audiotape. On one screen the woman is holding and slightly unraveling a tape while fingering it and explaining how the whole thing seemed enchanting and mysterious to a child, and also dangerous because of the fragility of the ribbon and warnings of her mother not to harm it, all to a young girl apparently destined to become a significant musician of some sort (we didn’t stay for the whole sequence to find out). On the other screen an older woman, identified only by her hands (but probably meant to represent the girl’s mother) is carefully operating a reel-to-reel recorder.

From there we watched videos of displaced folk musicians in their adopted countries, riding trains and performing in streets. These were alternately projected on four screens, each visual narrative on both sides of each screen.

Then we went into a large, darkened room with more than a hundred large bright round light bulbs in its ceiling. I say “darkened,” but the room got quite bright when the bulbs started flashing. A line of children in camp colors had accumulated in the corner of the room and were taking turns activating the mechanism. Each participant held two metal bars for about fifteen seconds, letting go once the device picked up his or her cardiac rhythm, identifiable as a change in the blinking cadence. A few seconds later the entire room went dark and then the light display began dancing on and off in the person’s heart rhythm.

We watched for quite a while, for the kids were delightful in their blends of intimidation, slapstick, and awe at propelling such a personal enormity into motion. We came back to the room at the end of our time in the museum to see if there was less of a line, and there was, so I will attest to the fact that seeing your own heartbeat fill a huge room in the form of waves of rhythmic pulses of light bulbs is profound; it grounds you anew in your own body.

We proceeded into the general exhibits, which consisted of several adjoining rooms of very diverse works in spacious settings. By “diverse,” I mean in every sense: decade of creation, style, color, texture, degree of representationality, degree to which the work leaves the canvass and extends onto the wall, shape of the frame itself (from minimally irregular to rolling jigsaws), overall cosmic dimensionality, etc. The works were aesthetically oriented in relation to each other, sometimes bunched, sometimes isolated; in fact, this building had the best museum feng shui I have ever encountered; I found it possible to be among separate art works in a state of relative relaxation for a long time.

I can’t begin to recount the variant color combinations and designs, but the whole landscape was pleasing that. Not seeing any sign beyond “Do not touch the art,” I asked a guard if photographing was allowed. He nodded, so I did a second pass and took a series of images of not so much the paintings and sculptures as the collective context of the people viewing, about thirty in all. Then, upon exiting the museum, I saw a picture of a camera with a line drawn through it. I can’t explain the discrepancy nor do I have to, but I did feel a bit like a thief slipping off with booty.

We returned to our neighborhood station as seasoned Metro riders (it turned out to be Sherbrooke), switching from the Green back to the Orange at Berri-UQAM.

Shot at 6:46 that evening, but I don’t remember what it is, perhaps something bright back from the Museum.

That evening we elected to get more use out of our one-day passes, so we took the Metro to Vieux Montreal on a lark. The actual gambit at street level was totally disappointing—heavily touristed with expensive restaurants, barkers quite successfully summoning folks into them by some magnetism I don’t understand, overcoming high prices and bad food. The architecture and port themselves had rich overtones and antique resonance, but they were a dead stage on which was set in motion simply hordes of misplaced, overamped people.

The best part of the outing was a family of four large friendly folks—Ma, Pa, boy, girl, Lebanese or Syrian—who helped Lindy and me find Old Town, in fact led us all the way there. We met them while wandering half a block from the Metro exit with no idea where to go. We hung with them for a good fifteen minutes, as they guided us back down the exit, through the subway, along a tunnel, and out the other side, all the time engaging with Lindy in a situation established by the fact that the woman spoke decent English but none of her kin did, though her husband had a lot to say to her in French, some of it with evident aggravation, none of which she conveyed to us. He probably wanted her to disengage

Yet, for whatever reason, without any spoken commitment or explicit indication, they did not abandon us and were even loosely protective, though intensely involved in their own debate about it. That is, they shepherded us at a slight distance like a Jovian moon. I am guessing that they were looking for Old Montreal too and had figured out at the same time as we did that they had made a mistake in leaving the Metro, though they never admitted that. For all we knew, they had changed their entire evening plans on the spot to lead us where we seemed to want to go, and then, as an afterthought, decided to eat dinner in Vieux Montreal too. Where we turned, they turned, and then vice versa, Lindy and she all the time chattering away at different levels of English, not only on finding the right streets but through Lindy’s narrative of how we ended up in their company that night (clear back to our departure from Berkeley in in June), a tale which seemed to fascinate our benefactress. Lindy even engaged in conversation with her about whether she herself would like to come to California someday; she would, her slight non sequitur, more a free association, involving a relative in LA whom she’d like to visit, a familiar trope

All the while the woman continued to haggle heatedly and at length with her husband in rapid-fire French (it is 11+ years since this encounter, and I realize that I have dreamed variations of it so many times that I have come to think that the original was a dream too).

Vieux Montrėal Graffiti—I have used this as my screensaver for the last 9 years.

We spent maybe forty-five minutes in Old Montreal all told after nixing plans to eat there and then. With some embarrassment, we watched a street busker who had accumulated a large crowd. That’s in fact where we lost our friends who continued walking down the cobblestone toward the port. A small fellow with a guitar and an unshaven swarthy Quebecois look (no racism intended, I like the style as well as its indigenous music and dance), was doing anything but indigenous music or dance. He was playing and singing “The Lion Sleeps Tonight” through a portable amplifier in imitation of The Tokens’ old hit while conducting volunteer tourists in successive rows of about ten self-conscious, often-cracking-up dancers doing various booty-shakings and shimmies. Alternately he was leading the rest of the crowd in a kind of collective karaoke version of the song as if the director of a hastily assembled glee club. About 150 people surrounded him, so you could barely glimpse the action. I have no idea what the interest or fuss was about, but people seemed to love him and were having a great old time. He was creating community, but if that was community, I wanted to be back on St. Denis looking for a restaurant. (I have dreamed variations of this too and thought the original a dream too until now).

An obscure highlight of the visit to Vieux Montreal was the corrugated wall of the Metro, painted in rainbow stripes that could have been hung in Musée d’art contemporain except that they went on for much longer than the museum could have accommodated; this art piece would have exceeded not only its frame but the outer walls of the building and extended onto the busy streets across vehicular traffic. It was that extensive a paint job. While we were admiring it, we were accosted by the unpleasant fellow from Nova Scotia. Like the family, he stuck to us for a while but without their benign intent.

After exiting at Sherbrooke, Lindy and I went back to St. Denis Avenue to look anew for a place to eat. We chose the Coréen place next door to the Tibetan restaurant. It was called Cinq Mille Ans, meaning 5000 years (of traditional Korean cuisine and culture, that is). Clearly a family venture, the place was both packed and understaffed that night. It took a very long time for the food to appear and, when we started to eat, our suspicions of what was being put before us were confirmed: we clearly had the wrong dishes; yet we decided to eat them anyway. For me that meant non-range-fed beef among the noodles. I rationalized that Canada was probably not as bad as the US in the matter of industrial farms, hormone- and antibiotic-packed meat, and assembly-line ritual slaughters. Whether or not this was convenient denial, t made for social sense and good etiquette to go with the situation as it played out.

We never got our teas either, so afterwards we tried to make sure we weren’t billed for them or the wrong dishes. We worked all this out with a man in his early twenties, part of the Korean family in charge but possessing more English than the others. He was clearly embarrassed for the state of things and insisted we return and let him make it up. I explained that we were driving from California to Maine and so we wouldn’t be back. He ignored that fact as incidental and asked when we were leaving town. Upon hearing that it was Saturday, he pointed out that there was plenty of time. In truth, there was only Friday, as we were going to Jia-lin’s dinner on Thursday. He was undeterred. “Friday it is,” he insisted. “I will make you a special meal.” Then he asked us to wait while he went to the kitchen; he returned with two green-tea ice-cream cones. We thanked him and left, though without a further commitment.

On Thursday morning we made plans to meet Wayne at his apartment at 12:30. In the course of our conversation, he gave me directions to a natural-foods market near his place (and not far from ours) at the corner of Rachel and Berri. Since we hadn’t been able to find one thus far, I walked to it right away, shopped for what we needed, and came back with a heavy bag and a sense of accomplishment.

Hilarious sight on my return: a female likely-professional dog-walker was leading five different sizes and shapes of pups on leashes including two large white Scottish terriers with a lot of hair in their eyes. A squirrel darted across their path. In unison they turned their heads and pulled like a team of huskies such the woman could barely hold all five even as she dug her heels into the ground and crouched low. After she got them under control and led them away, they continued, though not in unison, to look back over their hinds for a glimpse of the Sciurus carolinensis provocateur.

We used our subway cards one more time at their last hour to go a single stop to Mount Royal and then we walked that avenue to the park. It was a more varied, less upscale commercial neighborhood than our sector of St. Denis, with diverse markets, furniture stores, and variety shops. The feeling was college-like, suggesting a rehabilitated Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley or State Street in Ann Arbor.

We made it through the district to Mount Royal Park, a vast expanse rising uphill to a Cross set at its top, designating (in my mind anyway) Leonard Cohen’s city of saints. There we sat under a giant oak at the end of the initial expanse of fields, watching tennis players and gulls and taking stock of our lives and the enormity of what we were doing. At unexpected moments, the daze wore off and the sense of shock returned.

When we began counting gulls that had landed on the field (fifteen), we knew that it was time to climb some more. So we trekked uphill to the next rung where the density of trees increased, and from there watched the city clatter and breathe. Noon told us to head in the direction of Wayne’s, since we had only an approximate sense of the distance and time from there.

It was not a simple stroll. Well, it started out as a quiet walk but, as we got close to his street, the instructions coming from the opposite direction misled me, and we overshot it by walking from Rachel to Duluth to avoid construction and then had to walk the entire distance back plus some extra to get to Wayne’s place. What added urgency and made me doubly regret my error was that the whole sky suddenly darkened and, with rumblings of thunder, threatened a major downpour. We had left our apartment dressed for a warm, summery day. As it was, we found Wayne’s front door and rang the bell just as the first drops were landing. A deluge followed, beating and flashing lightning on the windows and sounding a diffuse din from the streets while we visited in the living room.

We sat on chairs among four playful kittens, all with designated homes once they were weaned. For now, they did the usual: attacked shoes, chased under furniture, and curled up in a ball at the foot of the scratch post, as we and Wayne recounted histories from our last meeting in 1976.

I would not have recognized him or more accurately not recognized him as Wayne, though I think I would have grokked that I knew this guy from somewhere. Thirty-eight years engrave indelible artistry, cell by cell, even as they crafted an immaculate body in the first place. The metamorphosis from child to young man (and young woman) and then to full-fledged adult and to elder is as gradual as it is profound and, like the shell of a tortoise, tells a thousand tales. Time’s transformations take on a rich flavor when so many decades intervene. Every old friend we had seen recently in Canada—Victor, Merrily, Andrew, Wayne—had re-costumed himself/herself from the cameo starring role of youth to the gist in which they had incarnated, leaving behind most of their affectations, conceits, pretenses, and primping.

Since 1976, Wayne had followed an interestingly fated route: he had moved to southern Vermont and lived in a barn while he tried to achieve the next level as a writer, finally giving the whole thing up as “I’m never going to be good enough to reach the top tier and nothing less is worth my interest or time, it’s Yeats or bust.” He printed t-shirts for a bit of income and ended up several decades later with a full Vermont-and-Florida t-shirt business employing ten people in Burlington to which he commutes maybe once a week while residing in Montreal. In the process he joined SABR (Society for American Baseball Research) and not long ago had taken a dedicated baseball journey to Cuba for which he wore a souvenir t-shirt, a typical Cubs jersey with the exception of an “a” in place of the “s.” It was not one of his company’s.

During the same period, he had married twice and had two children and a stepchild, all successful at one thing or another on the West Coast. In fact, his daughter who had gone to Haiti recently in the service of Oxfam was working on her PhD at UCDavis and, with her husband, had just bought a house on Francisco Street in Berkeley. They had had to overbid by more than twenty percent after missing out on a previous few. We had no such “luck” as a seller. Our original buyer withdrew his offer and we accepted the back-up and then absorbed some of the deferred maintenance to boot—our greater vicinity to the Hayward fault, plus that Kensington isn’t quite Berkeley or San Francisco.

Wayne explained how his grandmother ran Brown’s on a kind of scam, extending to the executives from Sullivan County National Bank tons of free meals, gratis rooms for their friends, and other perks, while continuing to get loans from without fulfilling the obligations. Once Citibank, or whoever, bought the local institution, its principals put a quick end to the practice and Brown’s quick folded; then it burned to the ground under different ownership.

The rain did not abate, so our lunch choice was limited to a Portuguese place on the corner, Wayne in a slicker, Lindy and me sharing an umbrella as we hastened. Lindy and he ate there. I didn’t—it was meat-oriented, cooked on spits right behind the counter, and I wasn’t feeling very good anyway. We sat at a table and exchanged more stories. The most memorable one (to me) was Wayne’s tale of the breakdown of his last marriage while on a home exchange in Paris: “If we hadn’t had our son and his friend with us, we might have killed each other.”

When Lindy asked if he was looking for another relationship, he feigned horror. He said he had never been happier than now. He liked his solitude, his non-interest in romance, and was very much into biking. In fact, in a few days he was leading a Quebec group of which he was the head on a five-day pedaling- and-camping trip along the north side of the St. Lawrence River.

The rain still hadn’t let up, so we “borrowed” Wayne’s umbrella to traipse back to our temporary Montreal home; that is, he could get another one.

The arrangement that night was for Jesse and Angus to come by our place and then for Jia-lin’s daughter Kelly to drive there a bit later, collect everyone, and bring us to Beaconsfield, a good hour away in rush-hour traffic.

A bit about Kelly: she was raised by Jia-lin’s parents not her mother who, in Mary’s account, did not want to be saddled with children. In fact, Kelly had had no contact at all with her birth mother for more than ten years and did not know where she was presently located but thought that it was maybe Bolivia, more likely that than China. Kelly had come to Quebec at age twelve and considered Mary her de facto mother. She had lived in Canada since then except for a marriage to a Japanese student in Montreal with whom she spontaneously moved to Japan. They were there for seven years until one night when he didn’t come home. After his departure was clearly ratified, she moved back to Canada. Since then, she had lived variously in Ottawa and downtown Montreal and was now ensconced at her parents’ house while she studied 3-D animation for a career change. Mary told us that Kelly was quite willing to run this errand, adding that she was very upbeat and good-humored like her father.

qWhile writing this entry, I asked Mary for a summary of Kelly’s career so I didn’t slight her, and she wrote:

“She is an accredited travel agent and worked in that field in Ottawa and Montreal. She also has a diploma from a private college as a make-up artist, but she didn’t get a chance to work in that field because her husband decided they should move to Japan. In Japan for seven years she worked as a nursery-school teacher, eventually becoming head teacher. Then when she came back to Canada she took an eighteen-month course of studies at Computer Data Institute in 3-D modeling, animation, and design.”

I am glad Kelly didn’t mention till late on our drive back that she also loved motorcycles and raced cars. The jaunt out to Beaconsfield was like a NYC taxi ride, though I’m not sure I trusted a girl from the People’s Republic quite as much as a New York cabbie but then, after all, what is a NY cabbie anyway but a guy from one or another people’s republic or Eurasian theocracy? Kelly went hair-raisingly fast, getting right up behind cars at full-commitment speeds. She explained that the rule of Quebec driving was Bostonian: “Seize space. If you don’t get it, someone else will.”

She had an interesting way of changing lanes that I was not familiar with. It was as though she put the car energetically in the next lane first with her aura and then the metal yawed to meet it. That is, her moves were mind, then matter: it vaguely felt like riding in a large suspender. She didn’t use her blinker because that was like giving her opponents an undue advantage. As to going too fast for anything but a crash if the car in front were in an accident or slammed on its brakes, she said, somewhat non sequitur, “Drivers in Ontario are worse. No, Quebec drivers are just as bad, but Ontario drivers are stupid too. They don’t have a plan. I always have a plan.” I was curious to know what the plan was, but I’m glad I didn’t have to find out. Her final answer was, more or less, “I got a motorcyclist’s license in Japan and, if you knew how hard that is to get, you’d realize that you can trust me.”

That’s good because we had no choice.

At the door in Beaconsfield, everyone stopped to admire Jia-lin’s garden, clearly the pride of the neighborhood, an extensive collection of flowers and herbs with a few large trees that, he informed us as he came out the door to enjoy everyone admiring his handiwork and curtly shout out names for anything anyone dawdled over, he had planted from scratch. Mary added:

“In bloom in the garden right now are different kinds of day lilies. But it depends on which month/week one visits, as it is a passing parade of hundreds of different blooms and blossoms. Almost all are perennials, except for some pansies etc. on the front stairs. So things follow their own rhythm and appear on cue in a succession of flowers starting in April or May and extending till late into autumn.

Joggers and cyclists like to make this part of their route to see the garden; one lady said she felt the garden was just inviting her to come and play in it. A local seniors residence always makes a point of driving their little shuttle bus by the house, even though we are on a crescent that is not en route to anywhere.”